Lyrics for final song below

The songs:

1. Wren songs John Neville and various wrens

2. Hunting the wren medley compiled/arranged by Dave Townsend

3. The St. Stephen’s Day Murders Elvis Costello and The Chieftains

This is the last posting of my Bill’s Midwinter Music series for this year’s holiday season. Today is the second day of the traditional 12 Days of Christmas and its pagan predecessors, which was long celebrated as a topsy-turvy day when everything was reversed and rules could be broken.

Following that tradition, I am breaking my own self-imposed rule by including tracks that have already appeared in one of my previous musical Samplers, the one from 1991. I know that I’ve already broken that rule this year (with Snow on Dec 17) but that was by accident; this is the first time that I have ever done it on purpose. I will also present my historical and social context background information first, before telling you about the songs themselves and the artists behind them. That part of this posting will include an addendum to Part 8 of the Ancient Origins essay that I included in my December 21 Solstice Day posting. (Don’t worry. You can skip that background information stuff if you want. Just scroll down until you get to the heading The songs.

In terms of some peoples’ current experiences of the holiday season, today is either a day of rest after a day of sugar- or alcohol-fueled Christmas indulgence, or a frantic day of shopping for Boxing Day bargains (although I think that the growing abundance of pre-Christmas sales may be signaling an end to that particular holiday-season “tradition” which only arose during my lifetime.)

Boxing Day, St. Stephen’s Day and the wren hunting custom

In most Provinces of Canada today is a statutory holiday, meaning either a paid holiday or a day when workers get paid time-and-a-half.

In Victorian times, as an offshoot of the movement to “Keep Christmas”, this was both a paid half-day holiday for workers and a day when their employers would give them a box of treats, food and a financial bonus to bring home to help their families celebrate the Christmas season. For servants in the homes of the gentry it became a full day off work as a reward for having had to do so much to prepare for the Christmas feast. They were allowed to go to their parents’ homes to celebrate their own belated holiday day, laden with boxes filled with gifts and leftover’s from the manor’s own celebrations.

This beneficence to employees was descended from a much older custom. In Roman times this topsy-turvy day, when all of the usual protocols of society were reversed, included not just a day of rest for the slaves, but a day when their masters and mistresses served their needs and desires. (I presume that the food was either leftovers or had been prepared beforehand.) This has also long been the day when the midwinter season’s luck-visiting began. All the wassails and Christmas carols that we now associate with the long run-up to Christmas were actually the soundtrack for the post-Christmas period from now until January 6.

In medieval times, the weeks before Christmas called Advent was a time of penance. For four weeks, all the way until Christmas Eve’s midnight mass, people could not eat meat or milk products, and singing (even hymns) was frowned upon. Advent was a time to be repentant for humankind’s sins, not a time to be happy! People could only do that during the 12 days long holiday that began with the holy day - a time when any work that was not essential to those days of celebration and prayer was forbidden. It was the only extended holiday the the year in the Church’s calendar.

It was the Church itself, and a Puritan government, that put an end to the”12 Days of Christmas.” The banning of celebration of Christmas for even one day began with laws passed by Cromwell’s Puritan Parliament. The laws were eventually rescinded but it was the protestant work ethic and the industrial revolution’s need to keep the factories running year-round that prevented the full extent of the holiday season from being revived after the religious turmoil.

But the day after Christmas, when the well-off were both in post-Advent good spirits and they had a lot of leftovers, was the best day to continue the various luck-visiting traditions that had existed since time immemorial.

Of all of the various European luck-visit rituals, none shows its very ancient roots more clearly than wren hunting. It has clearly continued since long before the time when this day came to be called St. Stephen’s Day. Not very much is known about Stephen except that he was stoned to death only a few years after Christ’s own death on the cross and he is considered to be Christianity’s first martyr.

His story is in the Acts of the Apostles; the fifth book in the Bible’s New Testament, written by the same hand that wrote the Gospel of St. Luke. That is why his day is given pride of place right after the day that the Roman Catholic church chose as the occasion to celebrate Jesus’ birth. (Having the date coincide with the Roman holiday of Sol Invictus, within the broader Saturnalia/Calends festival season, was not a coincidence. It meant that the Church did not have to try to stop its adherents from continued celebration of one of Romans’ most popular festivals.)

St. Stephen’s reputation has benefitted from that placement. Although there is nothing in the biblical account to support it, history has projected upon him (like it did with St. Nicholas) myths and legends that portray him as having been a very kind and generous person. This is probably because he inherited a place on the calendar that had long been a special pagan day of generosity.

There are various origin-stories associated with the curious wren-hunting custom (e.g., that bird’s loud calls had drawn attention to the place where St. Stephan was hiding from his persecutors.) None are very persuasive. But folklorists think that the ritual is related to ritual-sacrifice customs from long before the time of the Romans. The fact that ancient pagans had made animal, and even human, sacrifices to ensure the return of Springtime is both well-documented and supported by archaeological evidence.

I think that another possibility for the roots of the custom might have been the ancient custom of “Misrule” that had long been associated with this day in pagan times, and which continued through the very-Catholic medieval times. This day of the festive season was marked not just by role-reversal but also by doing the opposite of whatever was normal. Hunting of the harmless little wren is consistent with that. Wren hunting could be a mocking of hunts that were commonly held by the gentry at this time of year. The tiny bird is much too small to be hunted as food, and it’s diet of spiders and insects means that there was no reason to hunt it as an agricultural pest.

The traditional custom, in almost identical form, has taken place in recent centuries in Brittany, England, Scotland, Wales, the Isle of Man, and Ireland. It still survives in Ireland, although not in the gruesome manner of past times. Its more recent forms have been as a children’s activities, and the wren-hunting songs we have today probably all come from that usage, but like many old luck-visit customs it probably has earlier roots as an adult activity.

In its traditional form, wren hunting involved groups of people working together to chase a winter wren, a species that lives in the low bushes of the forest. The winter wren was the smallest winter bird in the forest (4” from the tip of its beak to the end of its distinctively stubby tail, and weighing only 9 grams) but it has the loudest and most complex song of all the wrens (see below.)

Until recently the winter wrens that we have out here on the Pacific coast of North America were the same species as those that were hunted in Northern Europe. But in 2010 there was a change to the taxonomy and those on the other side of the world and on the other side of the Rocky Mountains here in North America are now known as Eurasian wrens (Troglodytes troglodytes) and ours in Western North America are known as Pacific wrens (Troglodytes pacificus.)

In accordance with local tradition the hunters would either kill it or keep chasing until the tiny bird was so exhausted that it could be captured and caged or tethered. The trophy, sometimes decorated in regal attire, was then paraded through the town by its hunters wearing distinctive costumes and singing a traditional song, as the they sought donations from the community for the service that they had performed on their behalf.

Feathers from wrens sacrificed in this way were sold and considered to be a very powerful good-luck charm. I understand that in the 19th century, despite being Catholic, many Irish fisherman and sailors and emigrants to the New World would not consider going to sea without bringing a feather from such a ritual with them.

The parading through town and seeking donations part of the custom still survives in parts of Ireland, but these days there is no hunting for the little birds; sculptured models of them suffice. And the new custom is that the money raised in this way is donated to charitable causes. Here is a 1:44 television news clip from 1998 that I found on YouTube about the then-recent revival of the custom in Dublin. I may be a traditionalist, but this is definitely a break from the old customs of which I heartily approve.

Another transformation of an ancient midwinter tradition of which I approve is the demise of having a hunting day during the 12 Days of Christmas festival. In England the custom goes back at least until medieval times, after William the Conqueror (aka William the Bastard) declared that all game animals belonged to the Crown and could only be hunted by him or the gentry. But the midwinter custom was held by gentry throughout Europe so it must have been much older than that.

During the 12 festive days the Royal court, and the families of landed gentry who were not at court during Christmastide, would host hunting parties. Their tenants would join in by herding wild animals towards the hunters where they could be easily killed. Then the people were rewarded with a portion of the dead animals, providing meat for their seasonal feasts.

Originally, birds would only have been hunted with falcons. But the invention of the shotgun changed that. The earliest shotguns, or “Haile Shotte peics,” as they were called, date back to the 16th century in England, where they were used for hunting by the aristocracy, chief among them Henry VIII. They fired multiple projectiles making them useful for hunting small game such as rabbits but they were primarily used for hunting birds.

The English continued to refine their efficiency for hunting over the next three centuries, culminating with the application of percussion ignition at the beginning of the 19th century, and the introduction of a fully functional hinged breech in the 1830s. Finally, the advantages of a new cartridge that contained the primer, propellant, projectile, and firing pin, heralded the birth of the modern shotgun.

Thus, during the 19th century the tradition of the Christmas hunt evolved into the Christmas shoot, and as hunting became less rigourous for the hunter it also became exponentially more productive in terms of the number of birds that could be killed. The Christmas shoot became a true slaughter-fest of gamebirds throughout Europe and in North America.

At the turn of the 20th century the looming extinction of Passenger pigeons, whose population had dropped from billions to only a few remaining individuals over only fifty years, drew attention to how damaging this and other traditional practices had become. That led to the birth of the wildlife conservation movement. One of the symbols and benefits of that movement was the initiation of the Christmas bird count in 1900 as a replacement for the Christmas hunt tradition, and that new tradition continues to this day.

Each year near midwinter, on a specific day chosen by a local “Count Circle” coordinating committee, volunteers are encouraged to identify and report all of the wild birds that they can see. Some birders go out to find them in their natural habitats and keep track of their own personal annual lists as well as reporting their findings to the local coordinator. But anyone can participate just by observing and counting the visitors to their birdfeeders and reporting what they saw. The results are then tabulated by the local Count Circle so that they can be compared to previous years’ Christmas counts and identify trends.

This is North America’s longest-running citizen science project, and is now held in over 2000 communities. As the various local day’s counts come in they are submitted to regional and national committees who can also do comparisons. Truth be told, the process isn’t very scientific because this bird census can be greatly affected by weather conditions, participation rates can vary for other reasons, and other conditions can raise or lower the count. But these can be factored in to get a meaningful estimate of bird population trends, and bring public bring attention to the fact that wild bird populations are still rapidly declining. As a form of community observation of the Winter Solstice it sure beats the former midwinter shotgun slaughters.

Here is a 1:55 short clip from a Clancy Brothers concert in which they tell about their own experiences wren-hunting as children, and they sing the traditional song that went with the occasion. You can learn more about the Clancy Brothers and their version of the song from one of my postings last year.

Addendum to Ancient Origins Part 8 essay

Two thoughts have occurred to me since I posted the Ancient Origins essay about luck-visiting last Wednesday (Dec 21; the Winter Solstice.) First, I made much of the fact that the luck-visiting customs themselves seem to have been fairly stable while the songs adapt and evolve. But this is based upon what we know from relatively recent times; the past few centuries. I should have acknowledged that we don’t know if that has always been the case.

Perhaps there have been times when it was the songs and other specific elements of the ancient rituals stayed stable to provide continuity while the overall context and form of the luck-visiting custom did the evolving. Since my basic premise was that the luck-visiting custom is descended from the very ancient times from when our ancestors first followed the retreating glaciers into these northern realms, it follows that there might have needed to keep balance between stability and evolution for the custom to have survived for so long.

I cannot understand how those very early ancient ancestors perceived the world; my life has been way too different from theirs. Based on their tool-making we see that sometimes styles remained unchanged for very long times. For example, the Clovis style of making spear points lasted for over 1000 years. And for an important tool like that one I would expect innovation in functionality to trump tradition every time.

On the other hand, for an element of our ancestors’ culture like religious rites, or community traditions, one might expect a conservative approach to change. The Catholic Church retained Latin as the language of its services for almost 2000 years – long after the language was no longer used for everyday communication. And it kept Gregorian chant as its style of music long after it had ceased to be fashionable for secular songs. Its very archaicness and the sense of longstanding tradition that those elements gave the mass made it seem more important. So perhaps there have been times when the songs associated with the luck-visiting custom remained unchanged for very long periods of time even as the general form and rationale for the custom itself evolved.

My second addendum was inspired by an e-mail I received from Rosalind Adams, the matriarch of our local shape-note singing groups who also happens to have expert knowledge about English ballads and other folksongs. She wrote:

I reflected on the purpose as you stated it - to celebrate and bring people together. I am supposed to take a friend to the airport very early on Saturday, so she can go see her family in Saskatchewan. Of course, with all the snow she doesn't know if her flights may get cancelled. (Or I may not be able to get my car up the steep icy drive, too!)

This is always the way at this time of year, and I have to remember that the reason they started these festivals was because it was so snowy or so nasty out that no-one could do any real work outside or go anywhere. And here we in our crazy scattered out society have to all be crisscrossing the country in the worst of weather, just to keep the spirit of the festivals.

Totally mad, we are!

That got me thinking about the huge challenges that people faced in times past in order to continue the luck-visit custom; trudging through deep snow, howling winds, or pouring rain. In fact, there must have been many years when it was too dangerous or impossible to do it on the appointed day. I wonder what people did when that happened? In my fairly extensive research I have never read anything about that. Did they just give it a pass during those years? If that had been the case I would think that a few years in a row of impossible weather would have made it harder and harder to go out into the midwinter cold to continue the custom as a special midwinter occasion.

Alternatively, they may have just deferred their luck-visits until the weather became sufficiently clement for them to do so. That seems to me to be the more reasonable alternative, but there would have been some logistical difficulties. There needs to be coordination of timing for the custom to work: The households being visited needed to be ready to receive the visiting group. That wouldn’t happen if they had different perspective on when the weather had turned “sufficiently clement.”

I suspect that in years when the custom had to be deferred that there was such co-ordination. Either the well-off households sent messengers to tell others in the community that they would be prepared to accept visitors on a particular day, or the wassailers sent messages to the households in advance telling them on what day they intended to come. I can imagine that with storms following storms (as we are having this year) sometimes the deferral and rescheduling would have happened more than once in the same midwinter season.

Yet the preferred occasion has always returned to the most inhospitable time of the year. This suggests that celebrating the beginning of longer days, as soon as they could recognize that it had occurred, must mean a lot to the people at a very deep level. Even today, most of us celebrate the beginning of the new year at a very inconvenient hour in order to do it at what seems to be the right moment for the occasion.

If anyone has any information about either of these two areas of uncertainty, or indeed about any errors or oversights in my essay, please share them with me by email.

The songs

Today’s songs-of-the-day are actually two medleys and a pairing.

Wren songs are four tracks from John Neville’s Bird Songs of Canada’s West Coast. That 1999 CD includes 100 such tracks! And John has recorded more than 20 such albums; mostly from Canada but also from as far afield as the Scottish Highlands. As you can hear, John brings professional-quality recording equipment out into the bush to make his recordings. Note that this recording was made before the new taxonomy tht separates Pacific wren’s from Eurasian ones. This recording would be what is now known as a Pacific wren.

The purpose of these recordings is to provide a resource to assist birders who want to learn to identify birds by their calls. But he also wants people to listen and learn about individual birds and their habitat, and enjoy the sounds of the outdoors. He believes that ultimately the birds' will be better protected with more knowledge and appreciation of them.

You can obtain John’s recordings, either as MP3 downloads or CDs, from his website here.

Hunting the Wren is a medley arranged by British folklorist and traditional musician Dave Townsend comprised of four songs and a tune. It comes from his amazing 1996 Saydisc album A Celtic Christmas: Winter Ritual Song and Traditions from Brittany, Cornwall, Ireland, Isle of Man, Scotland and Wales.

Townsend’s Hunting the Wren medley is comprised of:

The King, a traditional wren-parading song from Ireland and Wales, first collected in 1879. (Roud no. 19109.) For more information about the song here is a good place to start. It is sung and accompanied on the concertina by Dave Townsend.

Can Hela’r Dryw (Hunting the Wren) is sung by Robin Huw Bowen. This is a very abbreviated rendition of a Welsh variant of a dialog song about wren-hunting. It was collected from the singing of Mostyn Lewis of Denbighshire/ Flintshire, but many similar variants have been collected from around Britain, where it is sometimes known as The Cutty Wren. (Roud no. 236. “Cutty” is a Northern England dialect word for short; in this case presumably referring to the winter wren’s distinctive stubby tail.)

This is the only known minor-key version of the song.

Other versions of this dialog are very familiar as humourous folk songs but most folkies probably don’t know about it having been a seasonal custom. Some versions transform it into hunting small rodents such as squirrels or mice.

The lyrics here translate as: “Where are you going? says Dibin to Dobin / Where are you going? says Richard to Robin / Where are you going? says John / Where are you going? says the never beyond / I’m off to the wood. says …. / What’ll you do there? says …. / Kill the little wren, says …. .”Shelg Y Drean (Hunting the wren) is a brief excerpt from another variant of the same song, this one being from the Isle of Man. (See here for information on the Manx variant of the ceremony. It is sung here by Emma Christian. Its lyrics translate as: “How will we get it down? said Robbin-the-Bobbin / How will we get it down? said Ritchie-the-Robin / How will we get it down? said everyone / With sticks and stones …. /He’s dead, he’s dead! said …. / He’s boiled, he’s boiled, said …. / Who’ll be at the dinner? said …. / The King and the Queen, said …. / Eyes to the blind said …. / Legs to the lame, said …. .”

The tune is The Wren Boys of Dun. Dave Townsend’s liner notes don’t say anything about its origins.

The Wren Boy’s Song is one of many variants from Ireland. This is quite similar to the one that the Clancy Brothers sang as children in their village of Carrick-on-Suir in County Tipperary but the liner notes do not say from which part of Ireland this version was collected. It is sung here by Colin McAllister, who accompanies himself on the bodhran.

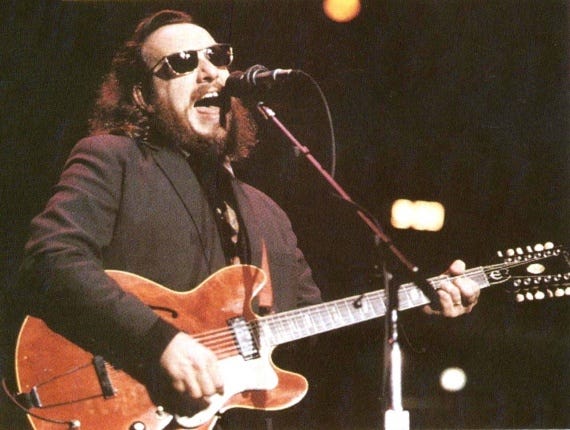

The final song is The St. Stephen’s Day Murders, which then flows into a tune identified in the liner notes as being called Christmas Eve. St. Stephen Day Murders, sung here by pop singer Elvis Costello, was written by him and Paddy Malony of the internationally-famous Irish folk band The Chieftains, founded in 1962. The Chieftains still exist with three of their original members (including Paddy) although they do not appear to have been recording or giving concerts since the Covid epidemic began. The song is from The Chieftain’s 1991 album The Bells of Dublin.

This song isn’t so much about the wren-hunting activity itself as about the role that it serves in getting the children out of the house while the adults are recuperating from Christmas, or alternatively, about murderous fantasies caused by family-gathering fatigue. As one unnamed writer puts it,

. . . the day where the previous day’s indulgences are to be dealt with, boarded up and cleaned out. It’s also the day where simmering tensions that may have been temporarily quelled by the season’s festivities start to arise, and the quickest way to assuage them is by drowning them in liquor and leftovers.

The St. Stephen’s Day Murders

by Elvis Costello and Paddy Malony

lyrics from hereI knew of two sisters whose name it was Christmas

And one was named Dawn of course, the other one was named Eve.

I wonder if they grew up hating the season,

The good will that lasts ‘til the Feast of St. Stephen

For that is the time to eat, drink, and be merry,

‘Til the beer is all spilled and the whiskey has flowed.

And the whole family tree you neglected to bury,

Are feeding their faces until they explode.

There'll be laughter and tears over Tia Marias,

Mixed up with that drink made from girders.

Cause it's all we've got left as they draw their last breath,

Ah, it's nice for the kids, as you finally get rid of them,

In the St Stephen's Day Murders.Uncle is garglin' a heart-breaking air,

While the babe in his arms pulls out all that remains of his hair.

And we're not drunk enough yet to dare criticize,

The great big kipper tie he's about to baptize.

With his gin-flavored whiskers and kisses of sherry,

His best Chrimbo shirt slung out over the shop.

While the lights from the Christmas tree blow up the telly,

His face closes in like an old cold pork chop.

And the carcass of the beast left over from the feast,

May still be found haunting the kitchen.

And there's life in it yet, we may live to regret,

When the ones that we poisoned stop twitchin'.

There'll be laughter and tears over Tia Marias,

Mixed up with that drink made from girders.

Cause it's all we've got left as they draw their last breath,

Ah, it's nice for the kids, as you finally get rid of them,

In the St Stephen's Day Murders.

Postscript

I began this month not knowing whether I was up to undertaking the time-consuming task of issuing a Bill’s Midwinter Music series at all this year. I had not been doing my usual preparation because last year’s burn-out was still too fresh in my mind. That is why the series began on Dec 2, rather than at the very beginning of the month like a proper Advent calendar should do.

I only decided to commit to it when the idea occurred to me that I had a lot of good music already selected in the candidate files on my computer, and that most people would be happy to receive them even without my usual background information, research, and thoughts about the seasonal music’s social and historical context. In fact, I know that many people would prefer just to get the music without my blithering on endlessly in essays that they have no time to read at this time of year. (But since you are reading this, at the very end of a long posting, you probably aren’t one of those people.)

As I wrote on the first day, my intention was to keep these short. That was a very good intention. But instead of sticking to that plan I re-discovered how satisfying it is for me to dig into the background of the songs, and to share my findings with others. I also re-proved the wisdom of the adage known as Parkinson’s Law: Work expands to fill the time available for its completion.

I have been spending all of my time though December on this project, ignoring all of the other things that I should be doing, including Christmas shopping. I must admit that I am relieved that the project is now completed (with this final posting being finalized on Friday, 3 days before it will be mailed and posted automatically.)

But I am very happy to tell you that I am feeling nothing like last year’s burn-out and am looking forward to doing this again (although preferably returning to my old practice in the days of CD Samplers when the project was completed well in advance of the midwinter season itself.)

Share this post