The songs:

Salut á la compagnie (Hello to this gathering) French part à Dieu song

Malicorne (recorded 1976)Legănelul lui Iisus (Jesus’s Little Cradle) Madrigal Chamber Choir (1980)

Iată vin colindătorii (Here come the Carol singers) ”

Gower Wassail Rasma Bertz & Salt Spring Island friends (2010)

Today, at 4:01 Pacific Standard Time, is the Winter Solstice; the shortest day and the longest night of the year. In recognition of that, today’s songs are wassails, a type of song that I believe (as explained in way too much detail below) has a very long association with this Midwinter occasion.

We now associate wassail songs (along with all Christmas music) with the long commercialized run-up to the holiday season, but historically wassailing was done in the days after the holiday. That is consistent with the fact that (as discussed in detail last year) our ancestors celebrated the Solstice several days after the actual astronomical event when they could confirm that it had happened through their own observations.

Last year my Bill’s Midwinter Music series included deep dive essays into the evolution of how the seasonal cycle had been viewed by our Northern European ancestors since the dawn of humankind, and how they came to view this time of the year as the beginning of the annual cycle. I was able to complete it as a musical series, but I fell behind in writing the story that my research was revealing. I promised to complete the story someday.

Today is my first installment in doing so. I had three more “Ancient Origins” essays in mind. The first would have completed the story about luck visit songs which is what I am doing today. After the background information below about the songs will be the eighth rambling essay from last year’s series to fulfill the that part of my promise.

Then there was to be a final episode in the “Ancient Origins” sub-series which would have summarized the beginnings and development of modern paganism, and finally, an essay would summarize and draw conclusions about the evolving celebration of Midwinter. It was that second one that burnt me out last year. I came to realize both that it was both a very challenging of a topic to research and that I am not personally comfortable even attempting write about it. It would have been about religion: I don’t do religion. So I have decided not go there.

The final part of that series is to be a final wrap-u essay that will review my research and analysis and draw conclusions about the evolving celebration of Midwinter. I still promise to do that – someday. Remember, still have good intentions to keep my postings brief this year, although I must admit that I have not been living up to my own expectations in that regard.

For reasons that will be discussed below, I have come to think of wassail songs and their counterparts from other countries as having a special place in our seasonal music canon. I believe that the traditional wassail songs we sing these days may be direct descendants of ones sung by our ancient pagan ancestors at this unique time during our planet’s annual journey around the Sun.

I am not saying that any of the traditional songs sung today are themselves that old. In fact, the midwinter luck-visit songs that we consider to be authentic and traditional are actually relatively new. But they are the products of a long chain of evolution to keep them relevant for changing times rather than the products of innovation. I believe that the ceremonies themselves evolve slowly but the songs evolve quite quickly. More about that later.

As discussed in the December 19 posting last year and in this year’s December 8 posting, wassailing (and its modern variant Christmas caroling) are regional English variants of a genre of community folk midwinter customs that folklore scholars call luck-visits. Similar ceremonial visits have been happening throughout Europe since time immemorial. And in fact, there are parallel ritualized ceremonies of lean-season visiting and generosity found throughout the world. In the scholarly world of folklore research, using principles similar to those in linguistic archaeology, this pattern of being widespread but with regional variations is recognized as an indication of antiquity.

The first song today, Salut à la compagnie, is a part à Dieu French luck-visit song for New Year’s Day. As I understand it, in medieval time the traditional custom of part à Dieu was that it was a stage near the end of well-off people’s New Year’s feasting when poor people could come to share in the left-overs in exchange for their offerings of entertainment and blessings for the coming year. The custom continued into more modern times as a children’s door-to-door New Year’s custom similar to our Halloween trick-or-treating.

This is a 1976 recording from France’s legendary folk-rock band Malicorne and is from their album Almanach that samples seasonal French folk music from throughout the annual cycle of seasons.

The next two Romanian songs illustrate how luck-visiting ceremonies and songs can adapt and change. As the country’s name suggests, its history was greatly influenced by having been an important bastion on the frontier of the Roman Empire. Like all Roman provinces, the people gradually became imbued with Roman culture. In the case of its people’s celebration of midwinter that included incorporating their own ancient Dacian midwinter traditions to co-exist with the Roman customs for celebrating the holidays of Saturnalia and Calends.

Their indigenous ancient luck-visit customs became blended in with the Roman ones, because that was always the case with lands under Roman rule. Roman authorities were very accepting of local religions and customs provided that the people paid their taxes and did not rebel against Roman authority: They patiently let time and economic influence do the cultural colonization for them.

The success of that strategy in Romania can be shown by the fact that this Eastern Orthodox country’s luck-visit custom is called colinde, and the singing itself is called colindam. Both words are derived from the name of Roman new year holiday of Calends (which gave us the word calendar.)

Roman midwinter traditions would also have absorbed customs from more recent waves of conquest after the Roman Empire collapsed. In general, the Romanian custom of colinde, as preserved in its rural areas, is pretty typical of its various European counterparts, from the Iberian Peninsula to Britain, to Russia. Indications of antiquity include that although the songs are traditionally Nativity story carols variants of the colinde ritual include blessings to enrich the fertility of the soil.

The first of the two Romanian songs in my medley is Legănelul lui Iisus (Jesus’s Little Cradle). It is a choral harmonization of one of the country’s many traditional folk Christmas carols. The song is performed by Romania’s Madrigal Chamber Choir and was recorded in 1980 on their album Romanian Christmas Carols.

The recording was made at a time when the caroling custom, and Christmas itself, was prohibited in Romania. Like the Puritans had done in England in the 17th century, the Communist government under Nicolae Ceaușescu banned celebration of the holiday! But his reasons for doing so couldn’t have been more different from the English Puritans. Ceaușescu saw Christian leadership as posing a threat to his one-party rule and decided to impose Communist Atheism as the state religion (or is that a non-religion.) He had the Orthodox priests arrested and executed and prohibited all forms of religious observance including colinde and the singing of Christmas carols.

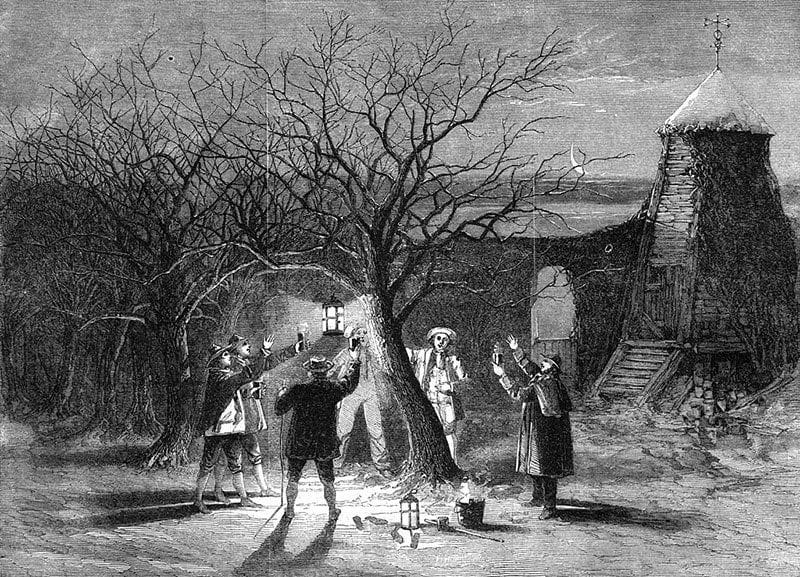

[Digression: You might reasonably ask: “But then how then did these songs get sung by the state-run Madrigal Chamber Choir and get recorded and CDs made by the state-run Electrecord recording company?” The answer is money. MCC, under the musical leadership of Marin Constantin, was one of the most highly regarded vocal ensembles in the world, and Romania was a very poor country. Recordings and concert tours by the group were a major source of revenue for Romania. Someone, perhaps Marin Constantin himself, suggested that a CD of their country’s rich heritage of Christmas carols and a related pre-Christmas tour (in costumes – see above photo) was a can’t-miss cash cow.

Ceaușescu agreed but with the proviso that the recording would be for export only and that there would be no in-country concert. And that’s how it happened. Well, with for one exception. With Ceaușescu’s agreement the Communist Party bought several thousand copies of the sought-after CD to give as the Party’s New Year’s gift to party officials. It was felt that they were loyal and intelligent enough to appreciate the songs only as being archaic examples of the country’s cultural heritage, and they wouldn’t be influenced by the songs’ lyrics. End of digression.]

How did the people react to this prohibition? Pretty much as you would expect (and the same as what had happened in England 300 years earlier.) In the cities, public acknowledgement of Christmas did not take place but its celebration continued in the privacy of people’s homes (even though they didn’t get the day off work.) In the rural areas the custom of colinde pretty much continued as usual, but with some discretion.

It still began on December 24, but that was nominally done only to keep up tradition: The people said that their new focus of the custom was to celebrate the coming of a new year under the Communist regime. What they sang during the visits rather depended upon the reputation of who was being visited. For trusty old friends it would be the old carols. But if they were visiting the home of the local party official they would sing the national anthem or another patriotic song. That person could then report what he saw: The people of his village were conforming to both the letter and spirit of the law.

In some cases they would write new secular lyrics to sing to the traditional Nativity carols’ melodies. That brings us to our next song, also from the same Madrigal Chamber Choir recording. It is called Iată vin colindătorii (Here come the carol singers.) The lyrics seem to be entirely secular although I must admit that my Romanian is rather rusty (or more accurately, it is entirely non-existent.)

Within a few more years there was a short but violent bloody national uprising. Romania ousted the brutal communist dictator and ended decades of communist rule in the country. It may or may not be a coincidence that it came on suddenly in December, and that Ceaușescu was killed by a firing squad on December 25, 1989. Romanians call this historic event the Christmas Revolution.

The last song today is the Gower Wassail. It was recorded in 2010 by Rasma Bertz along with some friends who live here in British Columbia on Salt Spring Island. The self-published album is called Winter’s Light.

This is a fairly typical English wassail song in that it doesn’t refer to the Nativity story or even mention Christmas. And like most of them it is named after the place from which it was collected, in this case, the Gower Peninsula on the south-west coast of Wales. It comes from the singing of Phil Tanner (1862-1950) when he was 75 years old. Tanner lived on western tip of the peninsula. The Gower Peninsula had been settled in previous generations by immigrants from Somerset, England so its local culture was more English than Welsh.

According to the unnamed writer of this blog:

Phil Tanner was born in 1862 to a family of weavers in Hillend. At that time Llangennith (or Llangenny as it was known locally) had about 400 inhabitants, most engaged in weaving, spinning or agricultural work, for much of peninsular Gower was self-contained through the paucity of good roads. Phil worked at various times as a weaver and as a farm labourer, but is best known as the folk singer of Gower, for with a prodigious memory he acquired a wide range of folk songs from travellers, gypsies and from oral tradition.

During his long life Tanner became well-known beyond Wales in traditional music circles and he is the source of many of the songs, ballads and mouth-music found in British traditionalist folksingers’ repertoire. He was also an important source for documenting other non-musical aspects of English folklore that had been preserved on the remote Gower Peninsula.

I might be inclined to include the same caveats for this song as I gave about John Jacob Niles’s Kentucky Wassail (see my Dec 8 post here) but similar lyrics (without a melody) had been collected earlier from Gower as early as 1884.

One of the earlier folklore collectors, Horatio Tucker, described the local timing and format for Gower wassailing in his account as he saw it in 1957 (see here for more details.) Wassailing there was done on either New Year's Eve or Twelfth Night (January 6.) The party carried with them a “Susan” – a large earthenware pitcher wrapped in a sheep fleece. This held the wassail punch, a special concoction that starts out as warmed highly-spiced ale. (Note that in the lyrics to Tanner’s variant of the song the Susan is described as already having ale and elderberry wine, and the visitors are asking for it to be replenished with cider.)

At each stop everyone, visitors and members of the household alike, are served from the Susan, and by convention the head of the household ensures that it is filled back up from his stores (which presumably has also been spiced and warmed on the stove.) The visiting party them goes on to their next destination getting increasingly inebriated.

I do not know whether the folks on Gower always same this same wassail song or if, like most English wassails, the verses were adapted or improvised to suit the particular household being visited. If so, I imagine that the later households heard some pretty creative verses sung to them!

Ancient Origins Part 8: Luck-visits, wassails, and Christmas caroling

Folklorists are in little doubt that luck-visiting is one of the oldest community customs in Europe, and that it dates back to pre-Christian times. The activities’ specific local and regional ceremonies and rituals vary, and the songs sung while luck-visiting may be secular or related to the Nativity story, but the basic form of the custom is ubiquitous.

It is rooted in a very reasonable way of dealing with a problem that has existed since our most ancient ancestors became humans. In the lean time of the year some people would die of starvation unless others in the community help them out, and some of the other people know that they have more food than they need to last the winter.

I am enough of an optimist to believe that in such a circumstance people who have enough want to help their neighbours who are starving, but they also do not want the recipients to feel ashamed of their need for help. People can also appreciate the mutual advantage of building social bonds with others so that they will help them when they themselves are in need.

Why wouldn’t our most ancient of ancestors, from the days of hunter-gathering, have seen it that way too, and provided their neighbors with the the sustenance they needed, and why wouldn’t those being helped expressed their thanks however they could? Storytelling and song around a warming fire would have been universally appreciated, especially on cold nights in the long dark evenings of wintertime.

To illustrate the concept of wassailing as having originated from helping neighbours in need, let me go forward in time to to a more recent era when we are certain that wassailing was occurring throughout Europe. In England, after the dissolution of the monasteries by King Henry VIII and until the establishment of government welfare programs in the 20th century, England had little by way of a social safety net. For some people in the countryside the threat of starvation in the wintertime was real. In many years when some people had a poor harvest or other calamity, their annual wassailing visits must have been very serious business indeed and not just ritualized social occasions. Those being visited must have known about their neighbours’ real need for more substantive assistance than ale or treats.

Luck visiting is, in essence, and exchange of services for goods. One way to keep the community strong is to continue with these exchanges in a ceremonial fashion even during times when there wasn’t a need from either party. Probably the people in communities that built strong social bonds by developing such community customs had a Darwinian advantage for surviving the harsh winters over those who didn’t.

So back to those very ancient times of our hunter-gatherer ancestors. I have no problem seeing why midwinter visiting became a valued annual ritual, despite the fact that travelling is hard at that time of year, and became a highly anticipated annual event that took place whether or not the stakes were starvation. I also have no trouble seeing how the formats of how those visits were conducted became traditions, and how over time those traditions evolved into community rituals for which the original purpose became irrelevant.

Over the years favourite stories would be told again and again, and given new life by the next generation’s creative storytellers; favourite games would be played and they too would evolve; and the same would happen with favourite songs. Some of those midwinter songs might have been reserved especially for this unique time of year. At the very least, the people got to share the warmth of companionship, entertainment and feasting to fill midwinter’s cold, dark, long evenings.

I like to think that some of the stories, songs, and other customs from those long-ago exchanges have been continuing to evolve ever since, and that some of the traditional wassails that we sing today might directly descend from songs that our very ancient hunter-gatherer ancestors visiting the caves of their neighbours sang to celebrate the Midwinter and their looking forward to the coming season of warmth and light.

Luck-visiting community traditions are very widespread and the general form that they take is very similar throughout Europe, This suggests that the format itself is rather stable. But the songs that accompany it vary considerably, and not only because of difference in languages.

That suggests that the songs themselves are quite fluid compared to the rituals and more subject to change and evolution over time. Given Europe’s turbulent past with regard to religion it is not surprising that ceremonies and rituals rooted in pre-Christian pagan times needed to either incorporate Christianity or be entirely secular. The path of least resistance would have been the former approach, especially when a cult of the Virgin Mary swept across Europe in the 11th century and people began to celebrate Christmas in earnest. (More abut that later.)

In England, traditional wassail songs only began to be collected in the latter 19th century. There had been a search for Tudor era “Christmas carols” earlier in that century. That search began because of the English romantic movement’s fascination with all things medieval, and was spurred on by a desire to create community traditions to support the Victorian era’s “Keep Christmas” movement.

Early 19th century carol collectors recognized that wassailing was a very ancient custom, but they believed that the secular wassail songs were a relatively new phenomenon. They were confident that the religious people of medieval times must have been singing religious Christmas-themed carols before the Puritan’s banning all celebration of the holiday, and then the licentious excesses that became associated with the season throughout the 18th century when Christmas’ pagan roots continued to make it’s celebration suspect.

As far as I can tell, wassailing never returned to urban areas after the Puritan prohibitions were lifted, or even if it had continued in such places to before that time. In fact, during the 18th century another ancient custom from Roman times associated with celebration of Calends, a day of “misrule” or the reversal of the social order, resulted in a fad of parodying wassailing emerged in urban areas. I suspect it was begun by rowdy young men who had studied Classics.

Instead of being visits intended to have mutual benefits for the visitors and those being visited, “Calithumpian bands” would come to the homes of wealthy individuals, or to concerts or other events where a genteel gathering was taking place, and play very loud and offensive “rough music” during the Christmas season. Rough music was not really music at all; it involved loudly “beating on tin pans, blowing horns, shouts, groans, catcalls” and it was intended to be as disruptive and offensive as possible. The visitors continued until they were paid to leave.

I have read no indication that this fad ever migrated to rural areas at Christmastime, but equivalents to this type of perverted “luck-visit” did occur in conjunction with the Springtime celebration of Plow Monday and the autumn post-harvest festive season. That

Early collectors like William Sandys and Gilbert Davies sought evidence of lingering practices of medieval Christmas caroling and authentic old carol songs from remote areas in England, that they believed would have been unaffected by the more modern seasonal upheaval. They were searching for more old songs like God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen. I don’t think they knew what we now know; that particular song with its profoundly religious lyrics had been written in 16th or 17th century City of London, most likely by someone with the city’s Waits – night watchmen who knew that they would be more likely to get a generous tip from the people they escorted home in the dark streets at night if they sang that kind of non-church religious song for them. In other words, God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen did not begin as Christmas caroling song at all (although it did become popular and widespread throughout England and was then sometimes adopted into that role whether folks thought of themselves as wassailing or Christmas caroling.)

For the most part, the early 19th century collectors didn’t find much of what they were looking for. They did find that people had customs from time immemorial of going from house to house singing at Christmastime, but they were mostly singing wassail songs that were entirely secular. Instead of concluding that that style of songs might also be a remnant from olden times they convinced themselves that the secular wassail songs had displaced the “true” medieval custom of luck-visiting with Christmas carols.

The early 19th century searchers were therefore not at all interested in collecting wassail songs with their relatively modern styles of melody and which clearly included contemporary and improvised lyrics. They were irrelevant to their objective of finding medieval Christmas carols.

Their counterparts who were doing archival research had better luck. They found both the words and carol dance melodies of medieval religious carol songs in the written records, but those were documenting the musical fashions of the gentry and the Royal court, not songs sung by common folk for visiting and entertaining neighbours at Christmastime.

But the desire to revive the imagined medieval tradition of Christmas caroling did not go away. So in the middle of the 19th century a spate of writing Christmas carols was begun. Some of them, like James Mason Neale’s Good King Wenceslas and O Come, O Come, Emanuel, and William Morris’ Masters in this Hall, even went out of their way to sound medieval.

We know that luck-visiting was indeed an ancient custom from pagan times that survived through the very religious middle ages, but as far as I know we have no idea what kind of songs the rural peasants actually sang while doing it during medieval times. Possibly they were indeed singing religious songs in the then-fashionable carol dance format. About four centuries earlier a popular movement had swept through Europe of venerating Christ’s mother Mary.

The medieval Mary Cult had not been initiated by Church leaders; in fact they had initially been opposed to it suspecting, possibly correctly, that it was a covert way to keep Pagan goddess worship alive. The movement’s popularity was so intense that the Catholic Church had to give in, including in 1163 by dedicating the huge new cathedral in Paris to Notre Dame.

But even now, Church leaders feel a need to emphasize that since she is not God, prayers and devotion to Mary must not be worship; it can only be veneration. (I don’t think that my parents made that fine distinction when they prayed their Hail Marys and kept track of them with their rosaries)

Among the impacts of the medieval Marian movement is that the people, not the Church, led the way in promoting Christmas to becoming a major holy day as well as midwinter’s principle reason for holiday. That was because that is the only occasion in the biblical accounts of Jesus in which Mary had a significant role.

It is very possible that old goddess-worship songs were kept alive through medieval times by transforming into Mary-worship (oops - Mary-veneration) songs. It is not unreasonable to think that some of those songs were used to defend the ancient custom of luck-visiting, transforming it from celebration of Midwinter to becoming a part of Christmas celebration.

The above-described recent flexibility in Romania shows how adaptable the music of the luck-visit custom can be to changing times. We know luck-visiting as a social activity (as distinct from people seeking midwinter food out of necessity) goes back to pre-Christian times. (It is well-documented that the Roman holiday Calends, which was celebrated with with which luck-visiting, was a secular, not religious holiday.) But what about before that. Did it begin as a pagan religious ritual (as as some fertility rituals suggest) and did its earliest songs reflected the pagan religious beliefs of their times? If so, when did luck-visiting cease being a religious rite an become a popular secular custom.

We also don’t know whether, in the long term, the constant state of evolution, adaptation and improvisation that we see in England’s 19th century wassails, and in some other countries’ luck-visiting songs, is the norm or the exception. Perhaps there have been long periods of history and pre-history when certain ritual songs remained stable and used continuously and unchanged over for very long periods of time.

Also, when people did begin to document the wassails themselves in the latter 19th century they were looking for the upbeat songs of the “worthy poor” not the begging songs of the actual poor (assuming such songs were different.) That suggests we have a considerable selection bias in the collection of traditional wassail songs. (We do have actual 19th century winter season begging ballad songs documented in printed broadside ballads, but they reflect songs for urban begging not what was done by the illiterate rural poor.)

I believe that the traditional wassails that we now hear and sing were drawn from those that were sung as part of the social customs that evolved to bind people together, and not the songs that may have existed side-by-side with them that were sung by desperate wassailers in times of necessity. I highly doubt that people whose real need was for food to survive would have been using their luck-visit opportunity just to seek alcoholic beverages and treats from their neighbours.

I suspect that if I did a more diligent search of the academic literature I would find that folkloric scholars have explored all of this in considerable detail. But like most of my research for my “Ancient Origins” sub-series last year, I am drawing my information primarily from non-academic sources. I expect that in coming years I will continue to learn more about the historical and pre-historical evolution of midwinter luck-visiting customs and the music that has accompanied them and I will keep you informed about what I discover.

The Victorian era Keep Christmas movement’s attempt to transform rural wassailing into faux-medieval caroling has made a degree of impact on our current popular culture. In my experience it is mostly in the image of professional Victorian-garbed singers employed to support our current very-commercialized holiday. I have never done it myself, but my sister Michele has so I know that it has occurred relatively recently and in communities where I have lived.

As a teenager Michele joined with friends to go Christmas caroling in one of the somewhat wealthier areas in neighbouring St. Paul, Minnesota. Her friends had been doing it for many years, and apparently the people they visited were well-prepared to welcome Christmas carolers. The people whose households they visited were not friends of the carolers, but when they came to the door the group was greeted and welcomed. After they had sung one or more of the well-known Christmas carols the group would be given a box of chocolate candies or a package of other Christmas treats, money, or a bottle of wine or spirits. She has especially fond memories of that last option since she and many of the other carolers were below the legal drinking age at the time.

There may still be some people who go door to door singing Nativity-themed Christmas carols for their neighbours, and raising money for charitable causes. But for the most part, the activity of caroling is no more a part of our current holiday traditions than is wassailing. They are both remembered but are not common current customs.

As for me, I consider it to be unfortunate that the formerly evolving wassail song canon has been frozen in the 19th century in the name of “authenticity” (and I appreciate the irony that the “traditional wassail songs” I include here and in my previous annual Samper CDs are part of that freezing process.)

I also consider it unfortunate that actual luck-visiting, whether with carols or wassail songs, is no longer a significant part of our celebration of the midwinter holiday season. But given current trends in censoring our seasonal music in the interests of inclusivity and respect for diversity, I predict that the lively and sociable custom of secular wassailing has better prospects of being revived someday than the intended Victorian transformation of that format into Christmas caroling with religious-themed songs.

Share this post