Today is Winter Solstice Eve. Actually the exact moment of the winter solstice occurs soon after midnight tonight – 1:19 a.m. PST to be precise – so tonight is the longest night of the year. These are excerpts from my 2005 Sampler. It was about midwinter and the Winter Solstice so I deferred it from its proper place in the chronological order because I thought the music would be more meaningful today.

My liner notes for that first Solstice Music Sampler focused on telling about why it happens and its longstanding cultural meaning for people in the Northern hemisphere. In short, observing the winter solstice it is the root of all of our midwinter celebrations including Christmas, Hanukkah and New Year’s Day. The music on that year’s Sampler complemented that narrative.

Special treat alert: Selecting the music and writing the notes for the 2005 Solstice Sampler was an interactive process, so it could just as accurately be said that my 2005 Sampler is a musical telling of the same story as I tell in the text. At the end of today’s write-up, after the sampler-making recollections, I include an edited version of that text. I am quite proud of this brief somewhat poetic essay so reading it is highly recommended.

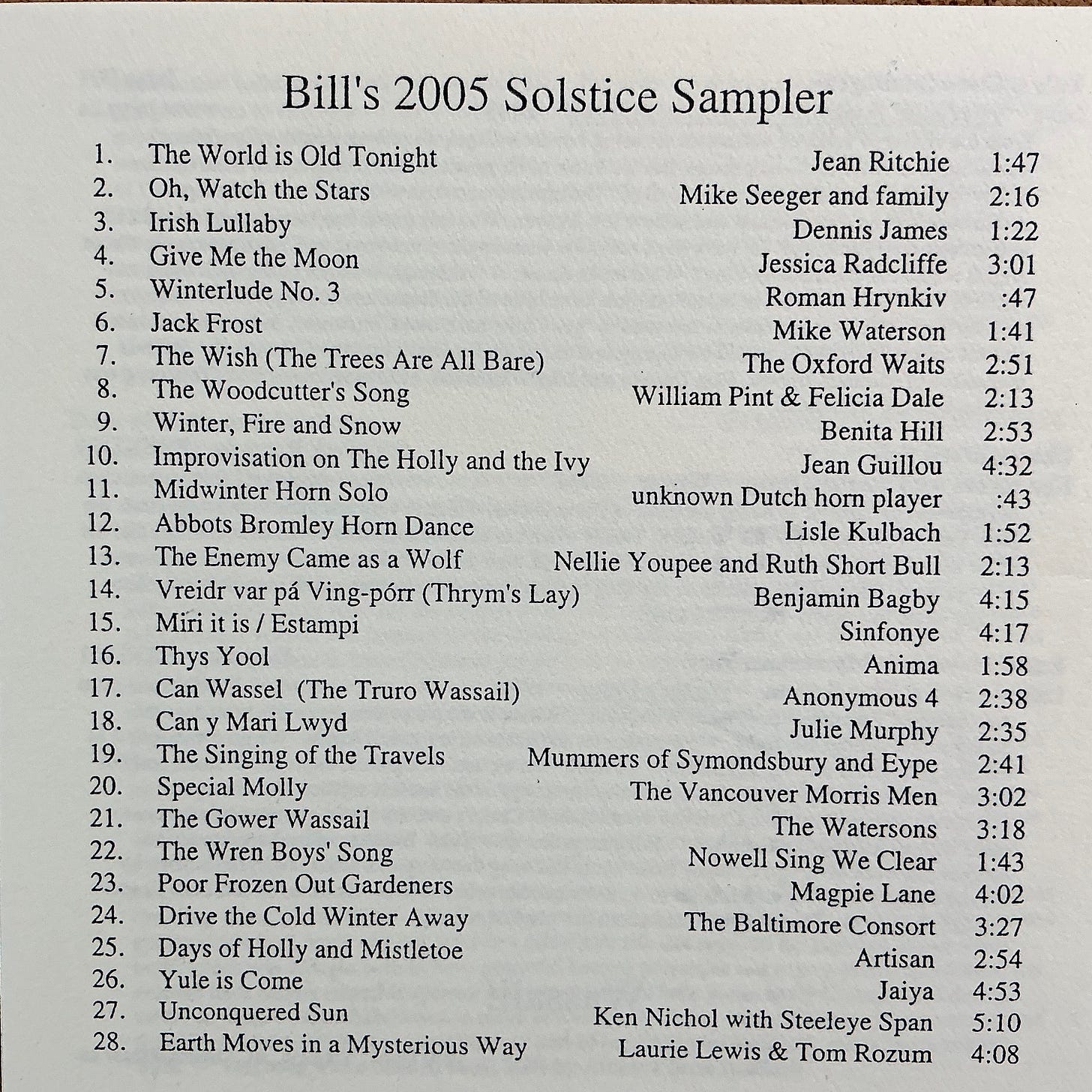

Playlist:

The World is Old Tonight Jean Ritchie 1:47

Winterlude No. 3 Roman Hrynkiv :47

The Wish (The Trees Are All Bare; abridged) The Oxford Waits 2:51

Yule is Come Jaiya 4:53

Unconquered Sun Ken Nichol with Steeleye Span 5:10

Music notes

The World is Old Tonight The words here are by the English playwright and writer Laurence Housman (younger brother of the poet A.E. Housman) from a play he wrote circa 1900. The melody is by Joseph Moorat who was the composer and arranger for a 1907 songbook for children called Nursary Songs. The singer is the legendary American folk-singer, dulcimer musician and folklorist Jean Ritchie (you can learn more about her from my essay here) and is from her 1989 album Kentucky Christmas.

Winterlude No. 3 This interlude was played and written by Roman Hrynkiv, who also made every part of this bandura, a traditional Ukrainian folk instrument. It is one of four interludes included on Al Di Meola’s 1999 winter nights album.

The Wish (aka: The Trees Are All Bare) abridged Oxford's Bodleian Library contains old broadsides (printed lyric sheets) containing many variants of this song from all around in England, the earliest being dated 1794. The Mudcat Café discussion group has an interesting discussion about this song in which Jim Dixon tells that he found a variant of it under the name Winter in an even earlier 1785 songbook. The variety of variants suggests to me that there must have been considerable oral transmission of the song as well as printed versions, since the differing texts show that there was a lot of “folk processing” going on.

The song also survived into the 20th century as a popular winter song Sussex. This rendition is based upon one of the Copper family's versions of it which closely resembles those of the earliest versions of the song. It is performed here by The Oxford Waits and is from their 2000 album Hey for Christmas.

Yule is Come (abridged) Many people today (including myself) want to rekindle observation and celebration of the Winter Solstice, not necessarily to replace the other holidays in this midwinter season of holidays but to honour its own unique ancestral place in our cultural heritage. For many years, on British Columbia’s off-the-beaten-path Mayne Island (which has a population of about 1200) the musical trio Jaiya awakened the Island resident’s to celebration of the changing seasons in accordance with the old pre-Christian holidays, and led in organizing community events to mark those occasions. Jaiya’s members, who are all also accomplished early music musicians, were Miranda Brown, Kim Darwin, and Lael Whitehead. This is from their 2003 album Firedance: Songs for Winter Solstice.

This song and dance was written by Jaiya member Lael Whitehead. Her liner note say: “The song opens with a fragment of a medieval Christmas chant. The plainsong swells briefly, then gradually recedes, as if replaced by the sounds of celebrations from an even earlier past.”

Unconquered Sun is performed here by the legendary British folk-rock group Steeleye Span that is having a 55th year anniversary tour this year. It is from their 2004 album Winter. The lead singer is Ken Nichol who composed this song for the album.

Sampler-making recollections

After I had compiled my 2002 Sampler, which was structured like a Christmas sandwich – a healthy portion of Christmas music between two thick slices of Solstice – I came up with the idea of compiling a sampler that would be exclusively be about the Winter Solstice. That required searching the internet for albums with that kind of music and buying them.

I was disappointed at how few such albums I could find. But I was eager to do such a sampler so I included a few songs that were not directly related to Solstice. In the sampler I wanted to avoid any songs that were reminiscent of Christmas, and I edited verses out of a few songs so they would be non-Christmassy. It turned out to be the most atmospheric (and most popular) of all the samplers that I ever compiled, and also the one that is least suitable for use as background music.

The stage was set with Jean Ritchie’s haunting The World is Old Tonight beginning a string of songs and tunes intended to draw listeners musically back in time to the world of our ancient northern latitudes hunter-gatherer ancestors, challenged by a season when they were deprived of the Sun's warmth and light, and when fire was sacred and essential to their survival.

It is not a coincidence that the mysteries that accompanied this season of deprivation and danger (as well as ice-cold beauty) was also the time of year when people were forced indoors and freed from the toils of daily rural life. Our ancestors huddled together around their hearths and communal fires, and this became a season of binding family-communities together throughout the lands that had previously been covered by Ice Age glaciers. Our ancient ancestors developed rituals, beliefs and customs which I believe survive to this day in just about all aspects of our celebration of the season. The last part of the sampler had songs that reflect how the ancient rituals are being reimagined and revived.

Usually, I begin the year’s project during the previous Christmas season by picking a theme, making selections of songs or tunes that fit the theme, then deciding how to structure them. Before this Sampler, writing the liner notes had usually been one of final steps in developing my samplers. But this time the story I wanted to tell in the notes turned song selection and note-writing into interactive process. The liner notes which told about the history of Solstice and its rituals and celebration, became a major factor in selecting the music from the various sources that I had begun seeking out three years earlier. Therefore, in some ways the 2005 compilation itself is a musical version of the text in the liner notes.

The Winter Solstice – excerpts from my liner notes

Our planet circles around our Sun with its axis tilted towards the North Star - Polaris. For a portion of each year the northern part of the globe is therefore tipped away from the Sun. Since long before there have been humans on this planet this geometry has created a winter season in the northern hemisphere in which the Sun does not rise as high in the sky, making the days shorter and the nights longer, and the land receives less of the Sun's life-giving warmth. The further north one lives, the more extreme is this effect.

In the northern latitudes of the globe in the lands that are now called Europe and northern Asia and North America, winter temperatures can frequently fall below freezing for extended periods. All plants and animals that evolved in or colonized this part of the planet needed a survival strategy for the quarter of the year when nature provides little warmth and nourishment.

Humans were no exception. When our ancient ancestors came north following the retreating glaciers from the last Ice Age about 10,000 years ago they had to develop ways to cope with the months when crops don't grow and game is scarce; when they needed shelter and fire to survive; when there sometimes are fierce storms; and when there always were few daylight hours and long, cold, dark nights.

By observing nature our ancient ancestors eventually recognized annual patterns. These included the fact that each day, from the middle of the warmest season to the middle of the coldest one, the Sun appears to rise slightly further south. In the other half of the year it appears to rise slightly further north. For many days while it is changing direction, it does not appear to move at all.

The word solstice comes from the Latin sol stetit: literally, "sun stands still." Long ago, at a time closer to the retreat of the glaciers than it is to the present, our ancestors built large stone observatories/temples to track the movement of the Sun and stars. But even with their astronomical technology the fact that the sun was rising slightly further to the north could only be confirmed a few days after it happened. It was only then that the people could be reassured that, although they did not yet feel a difference, the days would soon lengthen and the life-giving Summer will return.

In wintertime, when there is what we now call high atmospheric pressure, there are long, cold, and unless the Moon is near-full, very dark nights. On such nights there is little wind and the world is silent. Hoarfrost can form on trees and bushes, and the black sky is filled with bright stars. Our ancestors did not know why the same season that brought them hardship and danger also brought them this eerie beauty. Winter nights are a time of mystery and magic. When we look up into the midwinter sky we feel much smaller than when we are under summer skies.

In mid-winter, the Moon rises higher overhead than at other times of the year. According to the Farmers' Almanac the full moon of December is known as the Cold Moon or the Long Night Moon. The Almanac says:

During this month the winter cold fastens its grip, and nights are at their longest and darkest. It is also sometimes called the Moon before Yule. The term Long Night Moon is a doubly appropriate name because the midwinter night is indeed long, and because the Moon is above the horizon for a long time. The midwinter full Moon has a high trajectory across the sky because it is opposite a low Sun.

It is easy to see danger in the power and might of winter's dramatic storms and blizzards. But the quiet danger of frostbite and hypothermia from winter's relentless cold is equally dangerous. This sinister passive-aggressive side of the deadly season would have been fearful to our ancestors.

The practical reality of life for our ancestors was that very little outdoor or indoor work could be done during the midwinter. The daytimes were short, and there was no artificial lighting. Even after the advent of agriculture there were no crops to tend at this time of year, and the frozen or wet soil could not yet be prepared for planting. Animals needed tending, but chickens don't lay, cows give little milk, and the stock do not produce offspring at this time of the year. During harsh weather the animals were brought indoors to share warmth in the same buildings that the people lived in.

Humans are not naturally adapted to living in a northern climate, even for a few months. Our ability to make and control fire was absolutely essential for our ancient ancestors to settle here. Today, with insulated buildings, glass windows, central heating and electricity, we tend to take our ability to find refuge from winter for granted.

Our ancestors did not take fire's warmth and light for granted. For them, without fire's light they would be blind for 18 hours each day: Without fire's heat, they would die.

For our ancestors, fire was more than just a useful technology: it was beautiful and sacred, and winter life was clustered around the household and communal hearth-fires.

Our ancestors' brilliant astronomical technology did not give them the answers to their most important questions about winter: What was happening to their world? Why was it happening? To them, it was clear that some massive struggle was taking place in the mystical realm of the spirits and gods: The forces of cold, darkness and death had wrested control from the forces of warmth, light and life.

What could/must they do to ensure the return of summer and the continuation of life? Throughout the Northern hemisphere, ancient midwinter rituals centred around fire, light, and communal life.

The rituals our hunter-gatherer ancestors created to ensure summer’s return have constantly evolved and changed, especially when people turned to agriculture and community living during the Bronze Age. As time went on, symbols and practices that first began as important religious rituals have lingered in the culture as traditional seasonal customs even after they lost their religious significance.

For example, custom of decorating with evergreen branches and even trees at this time of year may be a distant descendant from displaying booty looted from the Holly King’s allies. Ancient fire ceremonies evolved into using fire, and now Christmas lights and Hanukkah candles, in a decorative way. Old shamanic figures might have evolved into Santa Claus, and the luck-visit ceremonies became Christmas caroling. Even the mistletoe, the Druid's most sacred plant and a reputed aphrodisiac (the crushed fresh berries resemble sperm) which had been banned from decorating medieval churches was trivialized into serving as a venue for chaste seasonal kisses.

We have a wealth of traditional wassailing and other luck-visit songs, but as far as I know, there are no old songs from fire rituals. We know that burning a massive Yule log was widespread, and basically similar everywhere in the “old world” northern latitudes. It was the core ritual/custom of midwinter until relatively recent times. But it died out rather quickly at about the same time as when lighted Christmas trees became popular.

(I am beginning to think that may not be a coincidence. Initially, Christmas trees had lighted candles instead of electric lights. It was obviously incredibly dangerous, yet that is what they did. But then, so were burning large Yule logs that were too way too big for the hearth. Perhaps they thought bringing a whole tree indoors was a fitting modernization for the important old custom. I need to mull that idea further before concluding that people had traded one kind of symbolic burning tree for another.)

As far as I know, we do not have any documentation of a single old Yule log song that has survived from that earlier activity, or even a song that sounds like it might be descended from one, and I have been keeping my ears open for such a seasonal song one for a long time now.

How can that be? Were the participants silent while doing the onerous job of bringing in that large and awkward symbolic object? Or perhaps the old ritual songs were unconsciously still considered to be too sacred to be trivialized into secular merrymaking songs? Or have their melodies been retained in Christmas songs whose origins are lost in the mists of time?

Although vestiges of the old rituals and symbols remain, our current seasonal customs have little of the drama or mystery or of the ancient winter solstice rites. One does not need to be a “believer” in anything to want to re-invigorate the Solstice spirit. Many lament the need to "put Christ back into Christmas." One can do that without ascribing to Christian religious theology to the holiday.

Similarly, finding new ways to celebrate the Winter Solstice as part of the holiday season does not require believing in anything in particular. It can be accepted as commemorating an important part of our shared cultural heritage. Newly written songs and new ritual-like customs are putting the fire back into the Winter Solstice.

Share this post