Special treat alert:

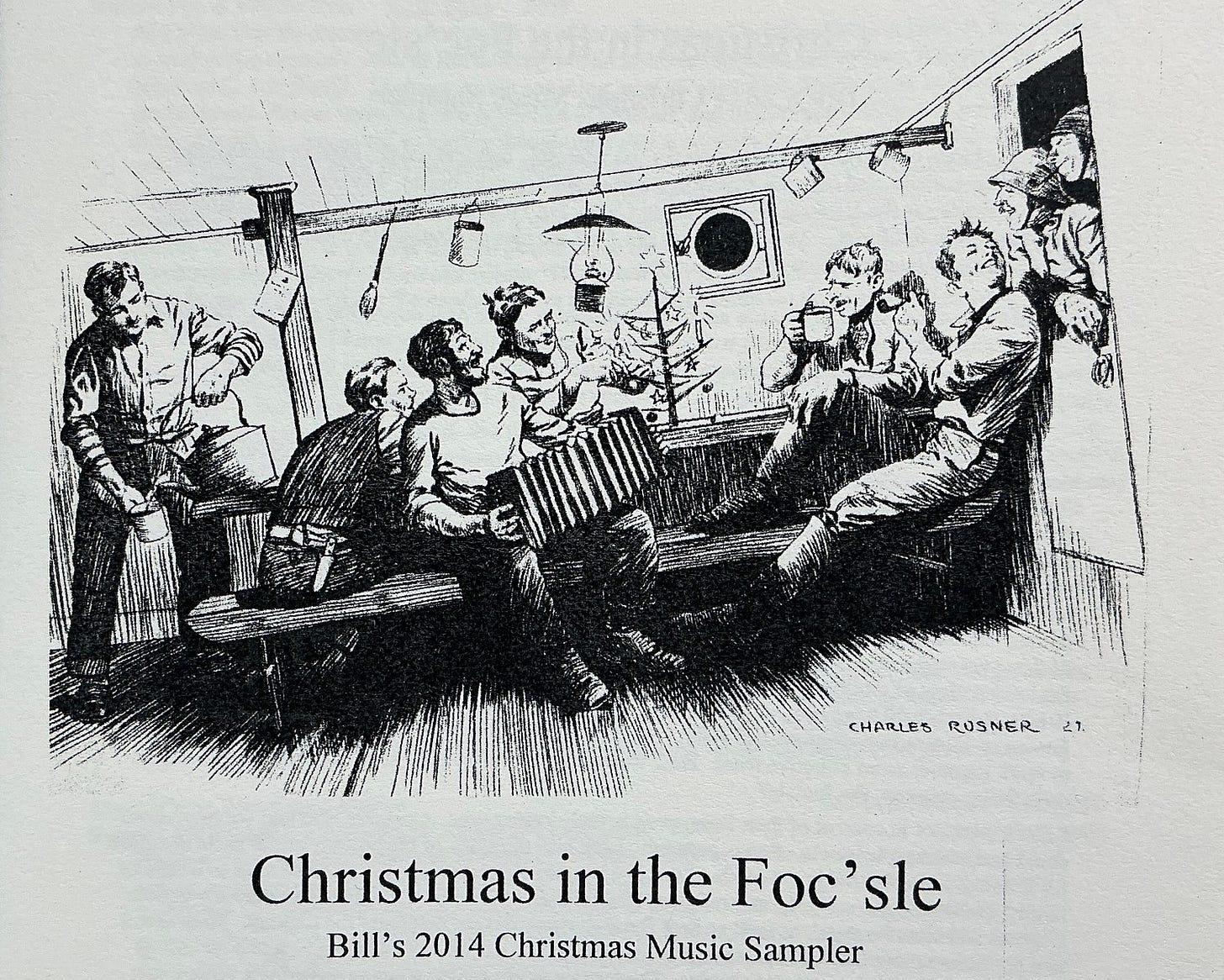

I like many kinds of music, but I have a few particular interests: Christmas and other midwinter music, of course, but also our rich legacy of nautical music such as sea shanties and maritime ballads. I actively sought out and reserved appropriate songs for a maritime Christmas music sampler that would combine those interests, envisioning both what the seasonal music on a 19th century sailing ship might have been like and how I would explain it in the liner notes. It took about twelve years until I was ready.

At the end of today’s posting, after the sampler-making reminiscence, are edited and expanded excerpts from the liner notes from my 2014 Sampler. They tell about and how Christmas music may have “gone to sea” both in the shanties that played an essential role in sailor’s labours and during their off-watch hours. I call the essay Christmas music on the tall sailing ships.

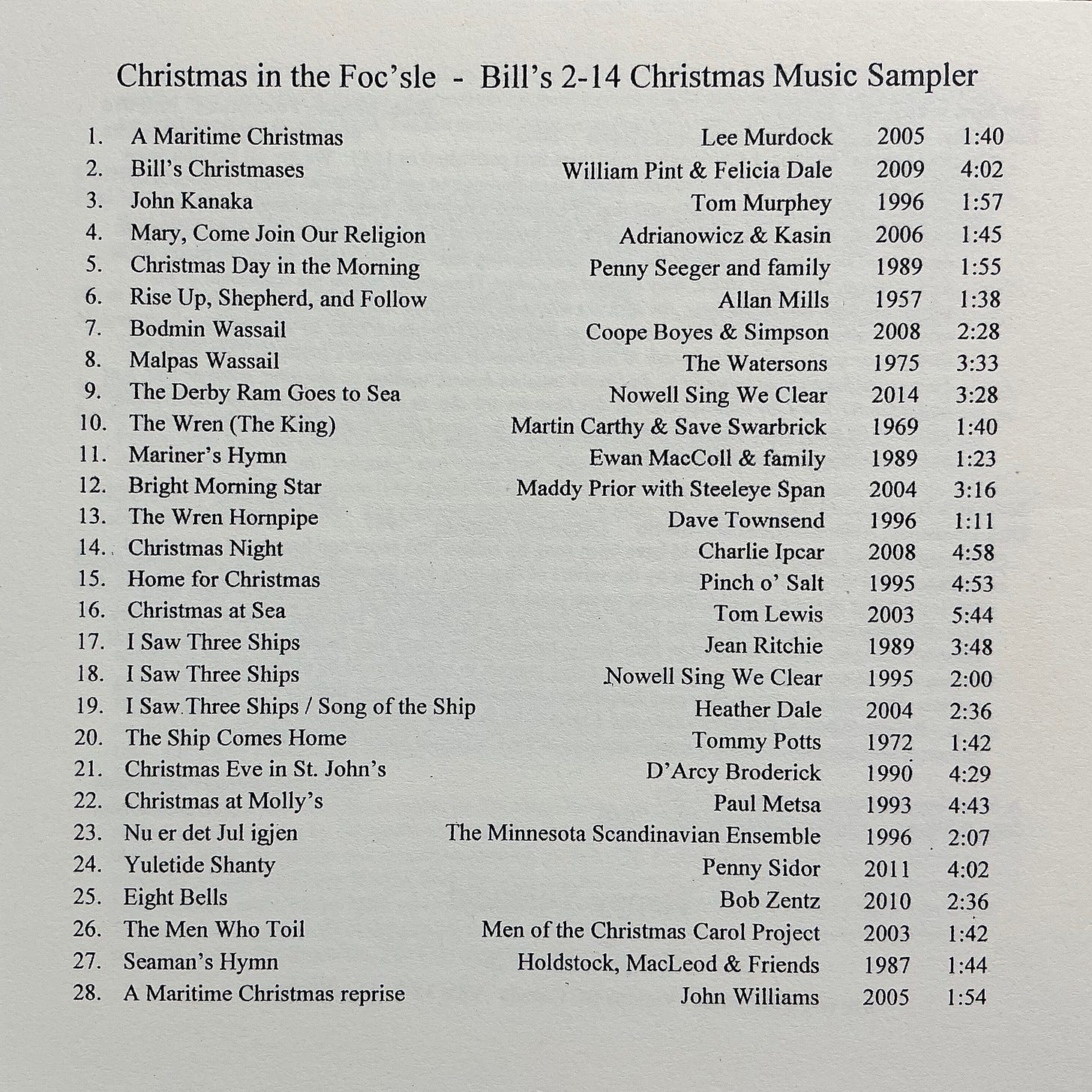

Playlist:

A Maritime Christmas Lee Murdoch 1:40

Yuletide Shanty Penny Sidor 4:02

I Saw Three Ships Nowell Sing We Clear 2:00

The Men Who Toil Men of The Carol Project 1:42

Bill’s Christmases William Pint & Felicia Dale 4:02

Eight Bells Bob Zentz 2:34

Music notes

A Maritime Christmas Folksinger, musician, author and singer-songwriter Lee Murdoch is the Great Lakes’ musical curator and educator. He uses songs and tunes to inspire residents around those five great bodies of water, where deep sea shipping comes inland, to become interested in wanting to learn more about how navigation on those lakes shaped their region’s rich history. This is from his 2005 CD/book Christmas goes to Sea.

Yuletide Shanty I got this song from Penny Sidor’s website (which is no longer active.) Penny lives on musical Gabriola Island, which has a population of about 4000 people, and which can only be reached from Vancouver Island where I live. I suppose that it would be an oversimplification to describe Gabriolites and others on the smaller Gulf Islands as falling into one of two categories: wealthy people who use it as their vacation get-away, and leftover hippies, folksingers and other artistic people. But that is about the state of things there. They certainly do have a very active folk music club, which Penny founded.

I’m sure she is the matriarch of folksingers on that musical Island, and is quite capable of keeping its unruly folkie crowd in harmony. (Gabriola folkies would consider the adjective “unruly” to be high praise. In fact, they would certainly be very offended if anyone were to called “ruley”.) Penny is an activist and one of her current passions is ensuring that Gabe will never have a bridge marring their splendid separation from what they consider to be stodgy, overcrowded, and too-busy Vancouver Island.

I Saw Three Ships In the study of folklore, geographic distribution and variety are considered to be evidence of antiquity. It is the nature of true folk songs that they are in a constant state of evolution, with different versions arising from different singers. Thus, having many variants that have been collected from different villages and towns is an indication of folk music age and authenticity. The songs that get collected and documented are just a snapshots in time of different versions of the song.

The familiar Christmas carol I Saw Three Ships is probably the oldest English language Christmas song that is still commonly sung, and also probably the oldest song of any type that is still part of English language popular culture. Part of the evidence for this is that it was known to have been widespread in the early 19th century, with many variants found in archival research that can be proven to be much older than that.

The version that we most frequently hear was collected from Cornwall by William Sandys and published in his 1833 study Christmas Carols Ancient and Modern. Since then, earlier versions have been found through both archival and field research, the earliest known one being in John Forbes’ collection Cantus, Songs and Fancies (1666). Since the carol format of song was already long out of fashion at that time, it is considered likely that the song is a survivor from the initial late-medieval carol dance/song fad during the reign of Queen Elizabeth.

This variant is probably closest to the original version of the song. It was collected in 1895 by the Rev. Sabine Baring-Gould from a boatman on the Humber Estuary on the East coast of Northern England. It recalls a documented historical event that occurred in 1164 when relics, including the purported skulls of the biblical magi, were transported by ship from Milan to Cologne Germany as a gift to that city from the Holy Roman Emperor.

The relics made Cologne a major pilgrimage site and the story of that voyage was popular throughout Europe in medieval times. Construction of its magnificent cathedral to house them began in 1248. It is the largest gothic church in northern Europe.

The word “crawns” used in this varient is an archaic word for “skulls”. Note that all versions of the song describe an inter-ship dialog regarding cargo, origin and destination. That is the type of exchange that would have been commonly heard aboard ships. This causes me to speculate that I Saw Three Ships may have originally been written as a seasonal shanty, and was only later adopted as a shore song by the addition of a superfluous first verse to some versions that that begins “As I sat on a sunny bank …”.

This is sung here by Nowell Sing We Clear, a holiday season quartet that entertained folks around New York and New England for over forty years with their ever-changing pre-Christmas tour until they retired in the year of the Covid pandemic. It is from their 1995 album Hail Smiling Morn!

The Men Who Toil Charles Dickens’ famous A Christmas Carol, was first published in 1843. We are all familiar from the many filmed versions of that novella, and the scenes in which the Spirit of Christmas Present takes Scrooge to see Christmas being celebrated by Bob Cratchit’s family and that of his nephew Fred. Less familiar are that Spirit bring Scrooge to see poor miners on the moor, the keepers of a lighthouse, and aboard a ship at sea.

From Dickens’ book:

“Again the Ghost sped on, above the black and heaving sea—on, on—until, being far away, as he told Scrooge, from any shore, they lighted on a ship. They stood beside the helmsman at the wheel, the look-out in the bow, the officers who had the watch; dark, ghostly figures in their several stations; but every man among them hummed a Christmas tune, or had a Christmas thought, or spoke below his breath to his companion of some bygone Christmas Day, with homeward hopes belonging to it. And every man on board, waking or sleeping, good or bad, had had a kinder word for another on that day than on any day in the year; and had shared to some extent in its festivities; and had remembered those he cared for at a distance, and had known that they delighted to remember him.

In 1996 eight of Edmonton Alberta’s folk and folk-rock singer-songwriters got together and wrote and performed a musical re-telling of Dicken’s timeless ghost story which they called The Carol Project. It retained that working title when it went into production and became a Christmas tradition for Edmontonians for the next twenty years. In 2006 it was made into a Bravo TV special. This song is how they told that forgotten part of Dickens’ story.

Bill’s Christmases The lyrics to this song are by poet and nautical historian C. Fox Smith. During a career spanning over 40 years Fox Smith wrote 14 books of maritime non-fiction including one collection of shanties, and had at least 650 poems published.

This body of work is recognized as having thoughtfully and accurately depicted seamen’s life, both at sea and ashore, during the days of the tall ships. Many of the poems, like this one, are from the point of view of an old sailor reminiscing about the past. The lyrics for this song were published in Punch magazine in December 1921. “Bill” was a recurring character in C. Fox Smith’s poetry. It is not clear whether the Bill poems come from the yarns of a single informant or if he is a composite drawn from various old sailors’ remenisences.

Fox Smith (which is a double-barreled last name) was not a salt-encrusted “shellback”, but still produced poetry and writings that were popular with the general public and sailors alike. The source of the writer’s insight came from befriending retired officers and seamen at fishing wharfs and other haunts. These were men who had worked on the deep sea sailing ships back in the latter half of the 19th century, which were then being supplanted by coal-driven steamships. Fox Smith listened carefully to their yarns as well as to their patterns of speech, learned about the details of their lives, and became accepted by the sailors themselves as an authoritative voice for the dying days of sail.

Fox Smith had been born in 1882 in the English midlands near the mouth of the River Mersey. Seeking new horizons, the already-successful poet travelled to Canada in 1911, settling down here in Victoria, working and living near the waterfront in what was then a bustling port town. In 1914 the poet felt the call of patriotism and returned to England, serving as an ambulance driver in France during the Great War and writing poetry in support of the country’s war efforts. After the war, Fox Smith lived in Hampshire near the great seaports of Bournemouth, Southampton and Portsmouth and turned to researching and writing about the days of sail as well as continuing to write poetry.

This poem was set by William Pint to a melody reminiscent of Good King Wenceslas. It comes from William Pint & Felicia Dale’s 2009 album Eight Bells.

Eight Bells On ships, the passing hours were marked by the ringing of bells every half-hour. Two bells … four … six …: Eight bells indicated a change of watch. One of these watch changes would occur at midnight. Thus, just like the wheel is an ancient metaphor in which the winter solstice became a new beginning in an ancient cycle, eight bells can also be a metaphor the beginning of a new cycle in the never-ending series of time, whether that cycle be a watch, a day, or a year.

This song, set and sung by Bob Zentz from his 2010 Closehauled on the Wind of Dream album, is another in which the lyrics come from the adventurous C. Fox Smith.

After the Great War the poet had continued to build a reputation and following, especially among sailors and former sailors, but the poetry went out of style and was forgotten after the writer’s death in 1954. This was partly because the work had continued to conform to traditional poetic conventions and eschewed the prevailing literary trends in poetry of the time, and also because the subject matter had gone out of fashion: It struck English professors as being romantic sentimentalism.

Now, as you can see from these two examples (the sampler had four songs based on C. Fox Smith poems!) that maritime poetry is being rediscovered – not yet by the academic English Lit community but by nautical singers seeking source material. With the poems now in public domain, at least seventy C. Fox Smith poems have been set to music by songwriters from Britain, both the East and West coasts of North America, Australia and New Zealand. (I have even done one myself - setting it to a faux music hall melody since it is a humourous poem that was published in Punch magazine.) Charlie Ipcar and James Saville have republished the full body of the poetry in a book (over 750 pages!) and posted all of the poems online here.

C. Fox Smith is again getting the recognition that she deserves. The C in her name stands for Cicely (pronounced as in precisely.)

Sampler-making recollections

It was about 2002, while I was compiling my “Solstice sandwich” sampler, that I began to reserve songs for other future special albums that went beyond the nativity/secular dichotomy that had previously been my main thematic distinction. Some, like the History of Santa Claus and the Christmas Angels samplers came together fairly quickly. This maritime Christmas music one is the most narrowly-focused sampler that I ever compiled, and it took 12 years until I had enough thematic music saved to bring the concept to reality.

Besides Christmas music I love maritime music – sea shanties, ballads, other songs about the age of tall ships, as well as recently-written songs about life at sea. One of my most common venues for singing has long been the Victoria Nautical Song Circle. It won’t surprise you to hear that I also have a large collections of albums in that genre, and that I find myself doing research about their history and about the life and times of the sailors who sang the old songs.

When I got down to compiling this year’s sampler I decided to try to make the styles of singing and instrumentation represent the kind of music that I thought would have been heard on a 19th century sailing ship. The songs might be new, but their spirit had to be old. I decided to only include songs and tunes that sounded like they might have been sung or played by sailors. That meant leaving out some really fine music in my file of candidate songs for this sampler that had the right topics and sentiments but the wrong kind of instrumental backup or that otherwise sounded too refined or modern.

There weren’t enough actual Christmas sea songs, but what documentation there is indicates that many shore songs went to sea, and I felt that I had a pretty good idea of what kinds of Christmas songs would fit the bill. So the sampler includes some authentic shanties that have no obvious Christmas connection, to give context for the non-nautical wassail songs and hymns that I do include. The Sampler does have a nautical variant of one that would have originally been a Christmas season song but has since become a year-round folk song (The Derby Ram) and which was collected by Captain John Robinson sometime before 1917 as being both a heaving shanty and forecastle song.

In my liner notes I found it necessary to explain the social context of this nautical music, and differing roles aboard ship of hauling and heaving shanties, and foc’sle songs. I also found it necessary to distinguish between what is known and my own speculations. That is all in the the essay Christmas music on the tall sailing ships (below) that is based on those liner notes.

The structure of the Sampler, after the introductory A Maritime Christmas and the ballad Bill’s Christmases, began with sea shanties (working songs) and 19th century Christmas songs that I thought would have been suitable to be adapted for that function by shantymen. It then goes into hymns that I think would have been sung on board the tall sailing ships.

That led into nautical narrative poems from that time that have since been set to become ballads. Actually, I had several more such Christmas ballads in my candidates file. Four of them were about the captain’s desire to get himself and the crew home for Christmas, and several were settings of Robert Lewis Stevenson’s dramatic poem Christmas at Sea. They all fit the theme perfectly but ballads are just so darn long that I only had space for four of them (including Bill’s Christmases.)

Next are three versions of the only traditional Christmas carol that tells a nautical story – I Saw Three Ships (which, when all of its verses are sung, is actually is a ballad too.) As you can guess, I had a lot of versions of that one in my candidates file for this sampler. I was rather proud of myself that I was able to include three different versions, none of which has the melody with which people are now most familiar.

After that it mostly has recently written songs about Christmas life at sea and sailors who are far from home in foreign ports on Christmas. The sampler closes with Eight Bells, The Men Who Toil, a seaman’s prayer for peace, and an instrumental reprise of A Maritime Christmas.

I was, and still am, especially proud of this particular sampler.

Christmas music on the tall sailing ships

The everyday life of common sailors aboard the tall 19th sailing ships is only partially documented, but some insights exist from the writings of former sailors like Herman Melville (who wrote Moby Dick in 1851 and Billy Budd, Sailor which was published posthumously) and Richard Henry Dana Jr. (Two Years Before the Mast; 1834.)

In the dying days of the tall ships, when they were rapidly being replaced by coal-powered steam ships, maritime chroniclers like C. Fox Smith took to collecting remembrances from old sailors. It was also only in those final tall ship years that people began to document the shanty songs that coordinated the work of the sailors, and the forecastle “forebitters” that sailors sang during their off-watch time. So not surprisingly we have no record of what music they had on special occasions and there are no holiday-specific songs even in ex-shantyman Stan Hugill’s authoritative Shanties of the Seven Seas.

But based on those scanty sources, we know that an individual 19th century sailor’s thoughts and feelings at Christmastime would have been just as diverse as people’s are today, shaped by his childhood experiences as well as by whether he was footloose or had family at home. His concept of when and how the holiday should properly be celebrated, or whether it should be celebrated at all, depended upon how and where he was raised, and whether he had fond associations with the holiday or only bitter memories. Like today, his desires regarding how the holiday should be observed would have been strongly engrained and deeply personal.

The crew, comprised of these varying individuals, was also much more culturally diverse than we are accustomed to today, but they shared the status of being among the lowest class and lowest paid of workingmen. In the late 19th century many deep sea sailors on American and British ships would have been ex-slaves from the American South, or refugees from the Irish potato famine or other recessions and wars. These diverse men needed to live together in harmony, and to work together as an effective team. How would they celebrate Christmas together on deck or in the forecastle (foc’sle) which was their living quarters?

Sailors were not in control of their lives, even in their leisure time. Captains also had varying views about celebrating Christmas. Some, certainly, were into the spirit of the holiday either as a festive occasion, in the mode of the 19th century movement to “keep” Christmas as a time when generosity was paired with religious observation. However many Calvinists and Puritans from both England and New England, as well as Scot Presbyterians, did not believe in observing the holiday at all: They saw it as a papist invention that was not sanctioned by the Bible – a relic from a pagan past and an unholy excuse for sloth and poor behavior.

The captain could decide whether the crew’s observance of the holiday would be supported by the issuance of extra rations, grog and light duty; or that a festive spirit was merely tolerated; or establish that acknowledgement of Christmas at all was forbidden. On the other hand, being a good captain meant “knowing which way the wind was blowing” and the results of banning the celebration of Christmas in both England and New England had shown that there could be unexpected consequences from such a prohibition.

But any plans that the captain or crew might have for celebrating Christmas were as much subject to the weather as to the captain’s views about the holiday.

No matter what the time of year, sailors enlivened both their work and their leisure time with music. Work songs were led by a song-leader called the shantyman. The heavy task of pulling on lines to raise and adjust sails, which required a short burst of exertion from every man, was coordinated by hauling shanties (rather than someone shouting “1, 2, 3, Pull!”) According to ex-sailor Richard Henry Dana in his 1834 book Two Years Before the Mast: “A song is as necessary to sailors as a fife and drum to a soldier. They can’t pull in time or pull with a will without it.” Hauling shanties were marked by one or two line solos from the shantyman to set the pace, and a brief refrain that was sung or shouted out by all of the other sailors as they all pulled together.

Long tedious hours doing tasks such as raising the anchor, pumping out the hull, or sanding the deck were relieved by heaving shanties, which had a steady rhythm and longer choruses for the men to sing.

Traditionally, the shantyman was chosen by his compatriots, not by the officers. The characteristics that sailors wanted in their shantymen were a strong clear voice that could be heard in the worst of weather, the ability to set a good working pace, a large repertoire of songs suitable for the various tasks, and creativity to entertain them by improvising new ones. Probably one of the most desirable traits would have been the ability to set a work pace for heaving shanties that was as slow as the bosun or the officers would permit, because once any such a job was done they would be given some other tedious task.

Perhaps because sailors work songs were so ubiquitous, no song-catchers thought to document shanties during the golden age of the tall ships that began about the 16th century. It wasn’t until the dying days of sail when they were being replaced by coal-powered steam ships that some people began to recognized that this musical heritage was about to be lost and people began to jot them down.

Thus, the shanties that we know of today were all compiled in the very late 1800s or the early 20th century from the relatively few ships that still sailed and from the memories of retired mariners. And the collecting was not done by the usual ethnographic collectors but by such folks as ship’s captains, members of their families who lived on board, or nostalgic travelers who wanted to document a vanishing maritime era.

The aim of these collectors was to document songs that were distinctive as shanty work songs, not the overall body of songs that sailors sang. Although some of the collectors make general reference to the fact that other types of songs were used for heaving or hauling, none make any reference to seasonal variation in the shanties the sailors sang. However, it seems likely to me that since even small changes in the ship’s daily routine would have been welcomed by the crew, and unless observance of the day was forbidden by the captain or the ship’s culture the creative shantymen would have marked the special occasion with Christmas songs from their own pre-sailing days.

They could have improvised special verses for the standard shanties, or led the work with familiar seasonal songs such as many of the wassails, Christmas carols or even hymns that fit the cadence needed for the task and had the sing-able refrains that mark all shanties.

We can trace the origins of many shanties back to the land. Folk songs, work songs from other professions such as stevedoring, logging, negro spirituals and field hollers, and music hall and minstrel show songs could all “go to sea” if they had the proper cadence, rhythm and call-and-response format, or if they could be made to fit the job. While there is no record of Christmas carols or wassail songs having been used as shanties, but many of them would suit the task perfectly, .

The medieval carole fad had ended in the 14th century but many of such songs continued to be sung in rural areas, and with their refrain lines many of those would also have been perfect for being converted into shanties. The 19th century had brought a revival of interest in Britain’s medieval heritage. The carol format included alternating short verses and sing-along refrains.

Collectors scoured the countryside for vestiges of the old music, and it became fashionable to write new Christmas music in the carol format to support the social movement to “keep” Christmas. Many of the both the actual medieval as well as the Victorian era Christmas carols that are still commonly sung today could easily be adapted for use as a shanty.

We have documentation of how many African-American and Caribbean spirituals and work songs evolved into shanties, and they were also commonly sung as forebitters (i.e., songs for off-duty recreational singing.) Even before the freeing of the slaves in the American Civil War, many sailors were African-American or Caribbean black men. As Stan Hugill, a Caucasian ex-shantyman who became a the pre-eminent shanty collector and historian from the early 20th century declining days of sail noted, many shantymen were Black, and their style of singing greatly influenced the style of singing done by non-black shantymen.

Among the types of shore songs that perfectly fit the shanty’s format, and that would have been very familiar to sailors from rural Britain as well as parts of America and Canada, were wassails and other luck-visit songs, and caroling songs. One reason that those types of songs would have been especially appreciated by the sailors is their content. Essentially, they are begging songs, but their heritage gives the practice an aura of social legitimacy.

Singing a wassail or caroling song aboard a ship might subtly (or not-so-subtly) remind the captain of the tradition of generosity to the poor at this time of year. The verses of many documented regular shanties asked for a boon, such as an extra ration of grog or better food. Sailors appreciated shantymen who could express their desires in a way would not be deemed to be inciting mutiny but which that might prove to be effective.

[As discussed above in my music notes, the version of I Saw Three Ships that is included in my sampler and in this set quite possibly originated as a sea shanty.]

In my research I found only two traditional sea songs that are clearly descended from luck visit songs. Pre-Christian horse cult ceremonies survived in many regions, especially Wales, as a luck visit custom, and one song that is distinctive to many such the luck visit rituals is Poor Old Horse. Variants of the song were traditionally used by sailors to accompany traditional ceremonies that were either held to recognize one month at sea (when the advance payment they had received before leaving port was considered to have been worked off) or when the ship crossed the equator.

Another luck visit custom from Derbyshire that evolved into luck visit playlets is also believed to descend from ancient animal sacrifice rituals. A song that was common in some of them was The Derby Ram (aka The Old Tup) which “went viral” in the 18th century as a non-seasonal tall-tale folk song. (George Washington is known to have sung it.) The song raves about the huge proportions and/or amazing powers of a magical animal. Shanty collector Stan Hugill includes various versions of The Derby Ram that were used as pumping and capstan shanties in Shanties of the Seven Seas.

Another variation on the luck visit custom was midwinter wren hunting. In the 19th century wren hunting was still common in Brittany, England, Scotland, and Wales, as well as on the Isle of Man and in Ireland (where it still survives in subdued form.) On the day after Christmas people (later just children) would go into the bush to kill a little wren, an ancient symbol of winter royalty. There were regional variations in how the wren-hunting custom was observed. In most they would parade the dead bird around the town, seeking food and money to give it a wake fit for its regal status.

In Ireland, part of the custom involved plucking out the feathers of the bird and selling them as good-luck charms. Sailors took this very seriously. One folklore collector said that an Irish sailor would no more go to sea without a wren feather than he would go without his knife. Since many sailors were economic refugees from the Irish potato famine, wren hunting would have been a fond childhood memory, and like other luck-visit customs, the activity had its own songs.

There is also no evidence from the shanty collectors that hymns were ever sung on the tall ships. On the other hand, they were shanty collectors, not hymn, carol, or wassail collectors. They may have not given such songs any notice even if they heard them being used as a shanty. We do know that some captains conducted religious services on their ships, with attendance being mandatory for all on board. (In fact, there was a hymn book published in 1826 especially for this purpose called The American Seaman’s Hymn Book.)

One rough-hewn hymn, called the Mariner’s Hymn, would have made either fine hauling shanty or a hymn for an onboard church service. It appears in the Millennial Harp, an American hymn book published in 1843 that has religious songs for all classes of society and was almost certainly specifically written by and for sailors. That hymnbook was intended for people who would be attending the camp meetings accompanying the end of the world and the second coming of Christ, which according to Samuel S. Snow’s interpretation of prophesies in the Book of Daniel would occur on Oct. 22, 1844. It has a call and response format that mimics the questions and answers that would have been commonly hailed between passing ships (and which is the format of I Saw Three Ships.)

I am not trying to suggest that the particular wassails, luck visit songs, carols and hymns that I have included in my 2014 Christmas in the Foc’sle Sampler were used as seasonal shanties in the days of sail, nor that when sung as a shanty that would they have sounded anything like we are accustomed to hearing. In practice, except on military ships shanties were not accompanied by musical instruments, and according to Hugill, sailors were not prone to harmony singing when doing their shanties’ refrains.

But the rhythm, cadence and rhyming pattern of these songs, and their inclusion of refrains and choruses, exactly matches shanties from the early 20th century collections. It is largely my speculation that if celebration of the holiday was permitted by the captain, sailors would have had a self-interest in filling their working hours with this kind of music at Christmastime.

The crew was divided into two workgroups, called the port and starboard watch, who worked on-and-off four hour shifts which were also watches. Weather permitting, both watches of sailors had no duties during the “dog watch”, which was from 4:00-8:00 PM. After their main meal of the day, and they had loaded their pipes or cheeks with strong tobacco, the music began. According to shanty collector Joanna Colcord, a captain’s daughter who was born and raised at sea:

“Singing, dancing and yarn-spinning were the order of the day; cherished instruments were brought out, perhaps a squeaky fiddle, or an accordion, beloved of the sailor and hated for some unknown reason by every master mariner I ever knew.”

The singing would have included solo performances of ballads as well as group singing of folk songs and the pop music of the day as performed in minstrel shows, music halls, pubs and other venues. Improvised harmony singing was common in British and Irish pubs, and beginning in the late 19th century barbershop harmony singing was all the rage in North America.

Since time immemorial there have been people with an uncanny ability to memorize long poems and to recite them entertainingly as storytellers or sing them as ballads. I can’t imagine why sailors, even if they were illiterate, would not have been among them. (In fact, some scientists believe that literacy is an impediment to this ability.) And I suspect that poems about life at sea would have been among the popular dog watch songs requested from such storytellers and ballad singers.

Two Christmas storylines are very common among nautical poems and ballads: Enduring a perilous storm on Christmas Day, and a captain’s resolve to get his ship and crew back to their home port for Christmas. Besides singing and telling stories about life at sea on Christmas, many sailors would have interesting tales about Christmases that they spent in exotic foreign ports. Is there a singer-songwriter worth his salty salt who could not set his own experiences to a tune?

As discussed above in the music notes, there is only one Christmas carol with a nautical storyline that is part of our “Christmas favourites” repertoire today – I Saw Three Ships - but it is known to have been widely known in the early 19th century, with many variants before the Victorian movement to hunt down old carole songs began. I imagine that it would have been popular among seamen, and many sailors would remember whatever version they had learned as children, especially if they grew up in a port town. I can imagine sailors comparing the versions that they had learned as children.

Finally, expressing a desire for peace on earth has always been one of the major themes of Christmas, and in Christmas music hopes for peace on earth remain one of the most enduring manifestations of the Christmas spirit for all of us. It certainly would be no less so for 19th century mariners. Whether they were serving on military vessels or aboard merchant ships they were at always at great risk, but never more so than during times of war when they faced the additional risks of having their ships sunk by enemy action or being forced by press gangs into naval service.

I have no trouble imagining what kind of quiet songs yearning for peace were song near the end of a Christmas Day dog watch. There is a relatively recent such song written by the Royal Navy sailor A.L Lloyd called the Seaman’s Hymn. It was for a 1955 BBC Broadcast commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar, based on a prayer supposedly written by Lord Nelson (that was the second-to-last song on my Christmas in the Foc’sle Sampler. It isn’t in this sampler-of-the-sampler because I was already over my 15 minute time budget but you can listen to it here.

Come all you brave seamen,

Wherever you’re bound,

And always let Nelson’s

Proud memory go round.And pray that the wars

And the tumult shall cease,

For the greatest of gifts

Is a sweet, lasting peace.May the Lord put an end

To these cruel old wars,

And bring peace and contentment

To all our brave tars!

Share this post