The songs

The Malpas Wassail – 4:12 – The Watersons

Please to See the King – 1:31 – The Nields with Ben Demerath

The Malpas Wassail I have a very large collection of Christmas and midwinter music, and I especially like authentic British midwinter folk songs. I have enjoyed authentic traditional music for all of my adult life and have a special affinity for authentic English folk music. I remind you of those facts so that this next sentence will be meaningful: This is my own personal “party piece” midwinter song, sung by my favourite British folk group.

As you will learn in the Dec 17 Ancient Origins essay, wassailing and it’s equivalent luck visiting traditions, is an extremely old Anglo Saxon custom. The custom itself, and perhaps the roots of its traditional wassailing songs, that may date back to much earlier than those times.

The Malpas Wassail (Roud 209) was collected from the far west end of Cornwall on England’s South West Peninsula. The song was collected sometime between 1928-1935 by the American song-catcher James Madison Carpenter from two sources: Bessie Wallace who lived in Camborne and Mr. W.D. Watson from Penzance.

The region was long famous for its bad roads and isolated fishing villages. That was the scofflaw region where the Christmas carol collectors Sandys, Gilbert and Davies went in the early Victorian era to find authentic medieval carols that had survived the Puritans’ banning of the holiday. (The even-older wassail songs were not collected at that time because the collectors of that era were looking for specifically for carols to support the emerging “keep Christmas” movement discussed in my Dec 3 essay about Hanukkah.)

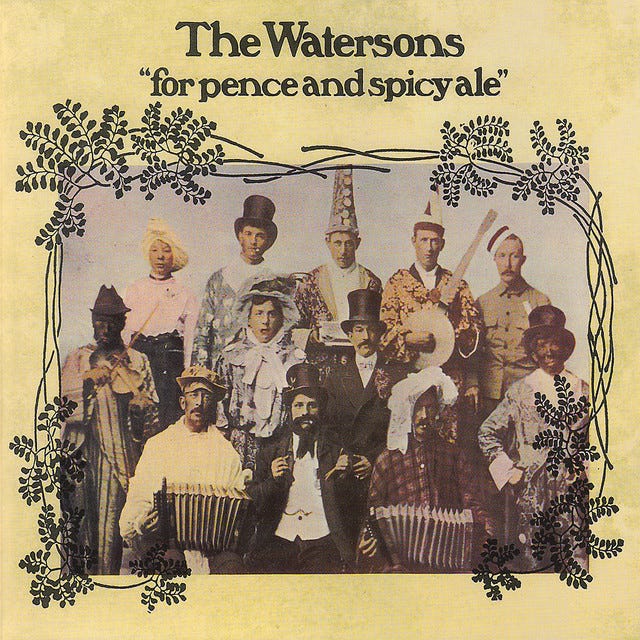

Don’t let me get started telling you about The Watersons. Suffice it to say that their a cappella harmonies were arguably the most influential force in the English folk music revival in the 1960s. Think of them as the folk music equivalent of pop music’s Beatles and Rolling Stones put together.

The group still exists in the form of Waterson:Carthy, comprised of original member Norma Waterson on vocals, her husband Martin Carthy on guitar and vocals, and their daughter Eliza Carthy on fiddle and vocals.

This recording was made in 1975 and is from the Watersons’ album “for pence and spicy ale”.

The lyrics are:

The Malpas Wassasil

Traditional midwinter song from Cornwall, EnglandNow the harvest being over and Christmas drawing in

Please open your door and let us come in

With our wassail

Chorus (after each verse):

Wassail, wassail

And joy come to our jolly wassailHere's the master and mistress sitting down by the fire

While we poor wassail boys do trudge through the mire

With our wassailHere's the master and mistress sitting down at their ease

Put your hands in your pockets and give what you please

With our wassailThis ancient owd house we will kindly salute

It is your custom you need not dispute

With our wassailHere's the saddle and the bridle they're hung upon the shelf

If you want any more you can it sing yourself

With our wassailHere's an health to the master and a long time to live

Since you've been so kind and so willing to give

With our wassail

The song Please to See the King is from Celtic luck-visit tradition of wren hunting. The song is associated with a midwinter custom that still continues in parts of Ireland and in other scattered locations (without actually killing and hunting the little birds anymore) that may be even older than wassailing. This too will be discussed in my Dec 17 essay.

Nerissa and Katryna Nields are a contemporary American duo who have been recording together since 1992. They record and tour with their 5-member folk-rock band as The Neilds, and have issued 20 albums. On this album they are joined by Ben Demerath whose folk career also goes back to the early ‘90s.

Personally, I think I can hear the Watersons’ influence on their style of a cappella harmony singing in this song, but they have made it distinctly their own. You can compare it for yourself because the Watersons sang this same song under the name The King’s Song in 1977. Listen to their version here.

According to the Mudcat folk-song database this particular wren-hunting song is from Pembrokeshire in South Wales, where wren day was held on St. Steven's Day; Dec 26.

The King’s Song

or Please to See the King

Traditional from PembrokeshireJoy, health, love, and peace be all here in this place

By your leave, we will sing concerning our King

Our King is well dressed, in silks of the best

In ribbons so rare, no king can compare

We have traveled many miles, over hedges and stiles

In search of our King, unto you we bring

Old Christmas is past, Twelfth Night is the last

And we bid you adieu, great joy to the new

Essay: Ancient Origins Part 5: Celtic, Germanic and Nordic Paganism [word count 1776]

On Tuesday I hinted where the story of ancient paganism is headed: Peoples’ formal beliefs and worldviews were beginning to become more like organized religions, at least for some people. First, let’s review what I’ve covered so far.

Before the invention of agriculture, people lived in small nomadic bands and their religion was based on animism’s spirits (or souls) that were associated with animals, plants, objects and phenomena from nature. We do not know if the spirits themselves had names separate from what they represented, but some of them were undoubtedly more important to others

Shamanism had also been born at that time. Individuals within the roving bands who had special knowledge, wisdom or skills were revered and began to develop a role of being spiritual leaders. Particularly wise/knowledgeable/skilled individuals probably developed a following beyond their own bands. But the basis for their leadership was personal, not institutional.

After the introduction of agriculture and the various technologies and complex lifestyle changes that came with it, people began to live in larger, stable communities, and power structures and kingships developed. Beginning in the city-states of Mesopotamia an individual person’s spiritual leadership could be magnified by their position in the social/political power structure, and organized religions were born.

These early Middle Eastern religions transformed the ancient spirits into people-like deities who lived in a social arrangement that was similar to a royal court and its related institutions. At least, that kind of polytheism is what the written clay records from the time say, and is what stone and bronze artifacts found by archaeologists depict.

But it is not unreasonable to assume that the evidentiary record may be skewed towards what kind of beliefs the rich and powerful had, rather than what the everyday working folk actually believed. Their high social status, especially for kings and emperors, made them like a link between everyday people and the gods.

Today’s essay begins about 1500 years after the city-state form of governance and these religions had been invented. The time period for this essay is from about 500 BCE to 500 CE. By that time bronze age technology, kingship, and its related polytheistic view of spirituality had spread like wildfire to other lands.

Another major new technology - making tools and weapons out of iron - was beginning to follow these social changes. From its earliest beginnings in Asia Minor the iron age began in about 1200 BCE and arrived at different times for different places. Like the bronze age, the iron age didn’t begin for a people when they first encountered metal but when they had the tools and technical skills (casting for bronze, and forges and forging for iron), and access to the necessary material, to make it for themselves.

Like the rest of the west coast of Europe, southern Britain had good farmland and the benefit of good weather because of the “warm” ocean currents. That land had been settled by agriculturalists soon after agriculture expanded into Northern Europe. The desirable landscape also meant that the region, like the rest of Europe, was ripe for invasion and cultural assimilation. A lot of mixing up and blending of cultures took place there.

As it turned out, southern Britain also had an abundance of gold, silver, copper, tin, and iron ore, as well as hardwood forests and coal, thus metallurgy and forging began early there too. (It is cheaper and easier to export metal ingots than raw materials, and once you have smelting and casting technology for bronze learning to forge iron is an easy next step.)

As mentioned in Tuesday’s essay, the bronze age Celts had arrived in Britain from the mainland in about 1000 BCE, pushing aside or assimilating the previous inhabitants. With commerce and travel primarily being by boat at the time, a population already used to bronze age technology, and with its rich resources, southern Britain entered the iron age in about 800, before anywhere else in Northern Europe. In the rest of the region the people didn’t begin that stage until 500 BCE to 800CE.

Metalworking, in itself, may have had some influence on peoples beliefs and worldviews, but I think the more important changes came from the introduction of kingship and its related organizational structures. These paved the way for the polytheism to be blended with local paganism throughout the Western world, producing the myriad of similar-but-different polytheistic religions.

There are roots and relationships between the various polytheistic religion in Asia and Europe, and there are various theories about their “family trees” of development. This, especially with regard to Greece and Rome, has been the stuff of “Classics” study for hundreds of years, and the academic world of Classics has several competing models and theories. If I were to follow that rout there is way too much for me to study up on for this series of essays. If anyone else wants to look into it you could start by googling “Proto-Indo-European religion.”

I admit that if I studied the material long enough I might find the answers, but from my quick eyes-glazed-over skim I noticed a few questions that the scholars do not seem to be addressing:

1. Did individuals become leaders in pantheon religions because of their wisdom and moral/spiritual leadership, or was religious leadership more of a political appointment for high-born people? (I suspect that it was the latter.)

2. Did participants really believe in the pantheon of deities or were they just going along with the prevailing norm? (I suspect it was mixed, but with many or most people just following the crowd.)

3. What did the people who were not high-born believe? (I suspect it was mainly old-fashioned animism.)

I did find some interesting things about what is believed to be true about the Celtic (which includes the Gaels), Germanic (which includes the Franks), and Nordic religions of about 1000 years ago. Animism appears to have been alive and well in all of them.

All three of these groups continued to put high value on sacred places, and those sacred places tended not to be enclosed in buildings. They all also erected stone circles, menhirs or carved stone monuments at many special places on the landscape. We can still see many of those places today. What we cannot see are the places where monuments and shrines were made out of wood. [Note: Archaeologists tend to study habitation and other building sites where they can expect to find extant artifacts. Ground penetrating radar, aerial surveying and other places to find the subtle evidence for past activities are still in their infancy. We are now at the dawn of a new age for learning about the past.]

In the short-lived bronze age and the new iron age, pagan sacred places in northern Europe remained natural features: springs, lakes, swamps and bogs; islands and mountains; and especially groves of hardwood trees and very old/large trees. When such a tree eventually died it’s wood was especially prized for use in sacred carvings or domestic architecture. When Christianity was expanding in Europe beginning about 600 BCE there are many examples of Christian missionaries (like St. Boniface) or conquerors (like Charlemagne) burning groves or chopping down sacred trees if the local pagans were resistant to conversion.

All of the northern European cultures put high value on rituals, which often took place at specific sacred times and places. Rituals included ceremonies and gifting, feasts, harvesting of ingredients and preparation of medicine and potions, and making sacrifices. Sacrifices could be valuable things that were destroyed or abandoned, or killing wild animals (especially dangerous ones like boars), but usually involved livestock or produce. Sometimes human beings were sacrificed or otherwise killed in a ritual manner.

They all seemed to engage in ritual burials which included burying valuable objects with the deceased. (The Viking boat burials began at a later time.) They all had divination, which usually involved foretelling the future.

None of the Northern European pagan religions of that period seem to be particularly interested in the personification and worshipping of their gods. Even among the highborn, people seemed to think of gods and goddesses more as story characters than as deities who interact with their lives.

The Celts, in particular, do not even seem to have had a clearly defined pantheon of deities, and unlike the Germanic and Nordic tribes their major late-year festivities were at Samhain (now Halloween) rather than at the winter solstice. This seems to be odd for a region that created Stonehenge. It is Saxon names for the winter solstice and its attendant festival seasons, Yule and Yuletide, that come down to us for the pagan names for midwinter rather than their Celtic or Gaelic counterparts.

At the time the Germanic and Nordic religions, cultures and languages were very similar, and according to archaeologist, classicist and historian Prof Malcolm Todd, based on archaeological evidence alone it is nearly impossible to distinguish early German sites from Celtic ones. Identifying the distinctive religious ways that midwinter was observed by these various cultures is therefore complicated.

[Digression: One characteristic that all pagan people seemed to have shared was that, just like we consider the “new moon” to be when we can see it, not when it astronomically happens, the winter solstice was the time when the sun could be confirmed as beginning to rise again in the sky rather than when the actual shortest day. That is natural considering that they did not have accurate timepieces for measuring hours and minutes, let alone seconds. Even with Stonehenge, this would have been a few days after the actual winter solstice.

In 46 BCE, the Julian calendar that was invented by astronomers and mathematicians was adopted, which included periodic adjustments with leap years. It was based on the solar rather than lunar cycle, and annual events could be accurately given dates. It was sufficiently accurate that it was not replaced until our current Gregorian calendar was adopted in 1582. Two date that was associated with the winter solstice (the word comes from the Latin solstitium - sol ‘sun’ + stit ‘stopped’) was determined to be Dec 25. The Roman observance of the new year had traditionally been when the observation that the solstice had happened could be made in favourable conditions, and therefore the first day on the new calendar was January 1, and its festival was called kalends.]

Just like all northern peoples around the world, midwinter was a sociable time of the year and they all undoubtedly had religious rituals for the winter solstice. However, it is difficult to separate which of these were religious versus which were social and cultural. Or perhaps more accurately, I should say which ones began as practical social and cultural practices but were given pseudo-religious meaning, and which ones began as religious rituals but were continued as social and cultural touch-stones after they no longer had significant religious meaning for people.

As with the Romans, when they invaded and conquered each other’s territories the northern tribes do not seem to have put a priority on changing the conquered peoples’ cultures and religions to their own. The result was usually a regional blending of the new with the old instead of one replacing the other. That might explain the relative ease by which Christians converted the inhabitants of northern Europe because the Church’s policy was to allowed the people to continue their earlier practices under the guise of new Christian meaning.

Artifacts and written history from the time are of very limited usefulness in understanding midwinter customs. Remember, Archeology has told us a lot about what happened at Stonehenge, but it can’t tell us what it meant for people other than the obvious relationship to the solstices.

Similarly, the written records at the time about pagan practices in the places we now know as France, Germany and Britain were also written by Romans. Unlike Flavius Josephus in the case of Jewish history, they were not insiders in the northern cultures and they certainly weren’t unbiased observers.

Interestingly for me, folklore, even with its pitfalls and missing parts, is the best tool we have for understanding this aspect of our cultural heritage. More about that on Saturday, Dec 18.

Share this post