[Note: A few people have told me that my reminiscence essay on Monday stirred up a few of their own memories of childhood in wintertime but they could not find the Comments section where they could share them. That is understandable because of the newsletter/blog/podcast package format of this series.

The newsletter you receive in your in-box does not have the comments section. When you click on the music it starts a podcast and also brings you to that day’s entry on the blog. It looks almost exactly like the newsletter (hence the confusion) but it does include the comments section. From there, entering a comment is fairly intuitive.

The “main page” of the blog is the archive. If you save it as a bookmark or favourite you can always easily get to it. Alternatively, you can always get there by starting the music from any newsletter. You could put a comment after any daily entry (they are in reverse chronological order) but it may be best to put them after whichever entry motivated you to comment. I hope this explanation helps.]

Today’s songs

Today is the fourth evening of Hanukkah. Banu Choshech is a well-known Hebrew children’s Hanukkah song. The lyrics are by Sarah Levi-Tanai (1911-2005), set to music that had been composed by Emanuel Amiran, also known as Pugashov (1909-1993). Sarah Levi-Tanai was a Yemenite-Israeli choreographer, composer and songwriter who was born in Jerusalem when it was still under the Ottoman Empire.

Emanuel Amiran’s family moved from Russia to Jerusalem when he was 15. He became a prominent writer of over 600 new/folk songs intended to provide a common musical heritage for Zionist settlers from many lands. In 1948 he became the Directing Supervisor of Music Education for the Ministry of Education and Culture for the newly-established State of Israel. The song is performed here by Los Angeles based singer, music educator, children’s performer and cantorial soloist Mollie Wine – known to children as Doda (auntie) Mollie. The recording is from her self-published Chanukah Pajamikah album, released in 2002.

The Candle Blessings are the three Hebrew prayers that were codified in the Talmud about 1600 years ago to be recited, chanted or sung while the Hanukkah oil lamps or candles were being lit each evening. There are several traditional melodies for singing the blessings but this one has become the most common. One translation of the blessings is:

1. Praised are You, our God, ruler of the universe,

Who made us holy through Your commandments

and commanded us to kindle the Hanukkah lights.2. Praised are You, our God, ruler of the universe,

Who performed wondrous deeds for our ancestors

in those ancient days at this season.3. (First Night Only): Praised are You,

our God, ruler of the universe,

Who has given us life and sustained us

and enabled us to reach this season.

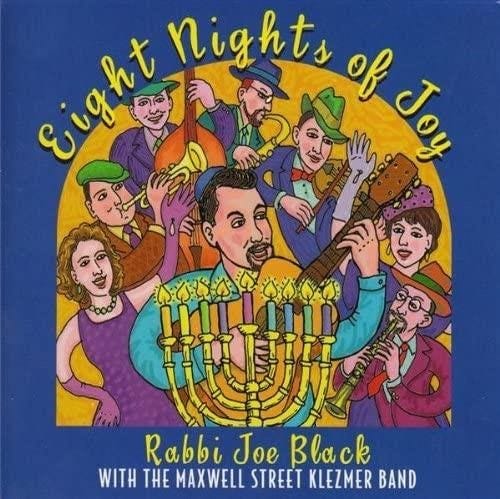

The blessings are sung here by Rabbi Joe Black who is currently the Senior Rabbi at Temple Emmanuel in Denver, Colorado. He is also a very entertaining singer-songwriter. This is from Eight Nights of Joy, a recording from a live Hanukkah concert that he and the Maxwell Street Klezmer Band gave in 2006 at Chicago's Temple Shalom.)

Ocho Kandelikas is performed here by Pink Martini, of Portland, Oregon, who describe themselves as “a little lounge orchestra.” The recording is from their 2010 seasonal music album Joy to the World. You can watch them performing this song here. It is fun watching cantor Ida Rae Cahana (in the red dress.) She doesn’t appear at all how I would expect a cantor to look.

The song was written by Flory Jagoda, who died peacefully this year at the age of 97. She was born in 1926 to a musical Sephardic family. Sephardic Jews were ones who had settled in Spain after the Great Diaspora (see essay below) but were displaced from there after the Catholic “Reconquista” of that country in 1492. Before that time, Jews, Muslims and Christians had all lived peacefully there together under Moorish rule for 800 years. That is when Flory’s ancestors moved to Bosnia.

In 1941 when Bosnia was attacked by the Nazis, Flory and her immediate family escaped to Italy, and in 1946 she moved to America as a war bride. The rest of her extended family and most of the members of the Sephardic community she grew up in stayed behind. They were all killed in the Holocaust. That spurred Flory to become a life-long teacher and activist for reviving and preserving their endangered Ladino language and the Sephardic culture. She wrote this familiar Hanukkah song in 1983 as an aide for teaching Ladino, the language of the Sephardic Jews that is rooted in Old Spanish.

Hanukkah is a time for rejoicing and one of the Talmud’s proscriptions is that there is to be no mourning during the festival. That will be hard rule for many people to observe this year, especially for people who first learn at this time that the indomitable, warm-hearted, and personable Flory Jagoda has passed on. To see what I mean I strongly encourage you to watch the following video of Flory performing Ocho Kandelikas at a music festival when she was 91 years old. Click on the image below.

Essay: Hanukkah’s second origin story [word count 1754]

Sunday’s essay discussed the Maccabee’s taking of Jerusalem and rededication of the Temple in the year 164BCE, and the then-unamed festivities that followed. The consensus at the time was that such festivities should continue to be held every year, and that was the origin of Hanukkah.

The circumstances for Jews after the first century of the Common Era were quite different from the heady days following that milestone in the successful rebellion against Greco-Syrian rule. While it brought brief independence, the rebellion had made the Jewish lands a vacuum as far as the imperial powers were concerned. For a while the land became a political football between the existing empires of the Seleucids and Egypt, and the newly-emerging Roman Empire.

Unfortunately, after a few generations the Hasmonian family dynasty and the Jewish priestly leadership that was closely aligned with them proved to be as incapable at managing their status as a subordinate kingdom in a world of empires as their predecessors had been. They tried to juggle and deceive their way to maintain independence, all while also dealing with internal dissent and enriching their own pockets, but given the strategic importance of the Jewish lands perhaps it was inevitable that they were conquered by the Romans.

In 63 BCE, the Roman general Pompey entered Jerusalem, sacked the city, and badly damaged the Second Temple that had been rededicated only 100 years earlier. At first, the Romans maintained the Hasmonian dynasty as their puppet government, providing them with a high degree of self-rule. Unlike Antiochus Epiphanes, the Romans were quite tolerant of cultural and religious diversity in the lands they conquered. They seemed to believe that, over time, cultural assimilation would prevail. Rome wanted only two things from their vassal states; political stability and prompt payment of taxes. The corrupt Hasmonian dynasty tried to maintain order but could not do it so.

The Romans got fed up with Hasmonians and in 37 BCE the Senate replaced them with Herod as their puppet king for Jerusalem and Judea. That appointment was somewhat unexpected since many senators advocated direct Roman rule. Herod himself was not from Judea but from Edom, another ancient kingdom south of Judea, although he had been raised as a Jew. But he was already culturally Romanized, because of his wealthy Rome-friendly father, and he had also already shown his loyalty to Rome’s interests (and gained a reputation for brutality) when serving as a Roman general and as the provincial governor of Galilee.

During his reign King Herod rehabilitated and expanded the Second Temple, and undertook a number of other impressive public works, and his brutality kept the people in check. But after his death his successors proved no more successful than the Hasmonians had been at maintaining order and ensuring prompt payment of taxes. Again, the Romans got fed up.

In 70 CE, after a five month siege, the future emperor Titus conquered Jerusalem, sacked and totally destroyed both the Temple and the city itself, and killed or exiled many of the Jewish people in Judea. In 93 CE, only 23 years after the event, the Judeo-Roman historian Titus Flavius Josephus estimated that over one million people were killed during and after the fall of city, and about 100,000 Jews were taken prisoners and sent into slavery or exile.

After that, the region was put under direct Roman rule. Rebellions continued but they were brutally put down, and many more of the Hebrew people had to flee Judea never to return. This exodus is known as the Diaspora, and is one of the most important and tragic events in Judaic history.

Obviously, we now know that the Jewish culture and religion survived this devastating event, but that wasn’t a foregone conclusion. Over the next few centuries, with no remaining civil or priestly leadership, religious scholars known as rabbis assumed the role of spiritual and cultural leadership for the dispersed Jewish people.

The rabbis recognized that the scattered people were at risk of assimilation in their new lands, or that the ancient beliefs, language, and other elements that gave them a distinctive identity, culture and religion would grow into separate factions. They identified the need to convert memories, traditions, rules, and religious texts that had been transmitted orally from generation into a clear, common understanding of what it meant to be Jews.

The first part of this job was relatively easy; determining which books were considered to be canon core holy writings of their religion and history. These are the books that we know today as the Tanakh (Jewish Bible.) The Tanakh does not include any of the writings about the victory of the Maccabees and the Hasmonian dynasty it inaugurated. This exclusion is not necessarily an indication that they considered these histories to be untruthful. The Maccabees books document a much more recent era of history than most of the other books in the Tanakh.

But the rabbinical logic may also have factored in that the disastrous Hasmonian dynasty was not one of their history’s best times, and remembrance of their relatively recent reign was probably not very popular in peoples’ memories. Perhaps more importantly, they were still living during the times of a Roman Empire that was quite touchy about such topics as commemorating successful rebellion against imperial rule.

Beginning soon after the Diaspora rabbis had also begun the much more difficult task of documenting knowledge that previously had only been in oral history, such as religious and cultural practices, stories, and rabbinical interpretation of the Tanakh. This involved four centuries of debate about to what to include, and resolution of differences between them so that there would be a degree of clarity regarding what it means to be Jewish. When they could not reach agreement they could at least document their deliberations.

The first reference to Hanukkah, after the books of Maccabees and a brief mention by the Judeo-Roman historian Flavius Josephus, was in the Mishnah, redacted about 200 CE, and other references to the festival collected over the next two hundred years.

By about 500 CE the rabbis had settled on core writings on these topics and they were collected together in the Talmud. By that time the festival to celebrate the rededication of the Second Temple (which was now destroyed) and the reestablishment of Jewish autonomy (also long gone) must have seemed like sad and moot part of their past. But the annual festival, already called Hanukkah (Festival of Lights) had become a part of the Jewish culture and an established part of the Jewish people’s religious calendar (and one of its few occasions that was joyous.)

The Talmud includes many then-current practices and stories from folklore (i.e., oral history) which would previously have been the traditional way to transmit this information from generation to generation. In the context of the Talmud’s discussion about the traditional protocols for dealing with the sacred lighting of Shabbat oil lamps (now usually candles) the rabbis also documented the appropriate procedures and prayers that had evolved for lighting the symbolic oil lamps during Hanukkah. While the hanukkiah (special Hanukkah menorah) itself had not yet evolved, the number of lamps, and the procedures and prayers associated with lighting them, are covered in the Talmud.

It is also in this context that the Talmud provides the only written record of the now-famous story about the miracle in which one day’s supply of oil lasts for eight days during the rededication of the Temple that had not been included in the Maccabees books.

The account in Shabbat 21b is brief (translation from the William Davidson Talmud):

The Gemara asks: What is Hanukkah, and why are lights kindled on Hanukkah? The Gemara answers: The Sages taught in Megillat Ta’anit: On the twenty-fifth of Kislev, the days of Hanukkah are eight. One may not eulogize on them and one may not fast on them. What is the reason? When the Greeks entered the Sanctuary they defiled all the oils that were in the Sanctuary by touching them. And when the Hasmonean monarchy overcame them and emerged victorious over them, they searched and found only one cruse of oil that was placed with the seal of the High Priest, undisturbed by the Greeks. And there was sufficient oil there to light the candelabrum for only one day. A miracle occurred and they lit the candelabrum from it eight days. The next year the Sages instituted those days and made them holidays with recitation of hallel and special thanksgiving in prayer and blessings.

For many people, including many rabbinic scholars, the convenient emergence of this story 600 years after the event is suspicious. However that is how it often is with oral history; collected only once and with no other extant evidence for verification. However, another factor to consider may be that, as any artist can tell you, accuracy is not necessarily most important element of Truth. And as any folklorist can tell you, the actual veracity of a legendary story is not necessarily related to its Meaningfulness to a people. (The European legend of the English King Arthur, first documented in writing in France, is a good example of that principle.)

In any event, it appears that certainly by 500 CE, and probably before 93 CE, a distinctive ritual for the nightly lighting of the hanukkiah as the core religious element of the Festival of Lights had already evolved. Also, Hanukkah’s observance at that time was family-based, rather than held at a religious venue and led by religious leaders. Even in those days commemoration probably included oral transmission of history and culture, and Hanukkah had continued to be an occasion for joyous secular celebration with only a brief nightly religious ritual.

Very early the originally nationalistic/religious festival had already evolved to being one that celebrates renewal (in this case, rededication) as well as fire and light. This is just like festivities held around the time of the winter solstice by every other culture in the agricultural world. Perhaps around the time of the winter solstice, fire rituals may have already existed in the Jewish culture long before 164 BCE, and the Maccabees and the oil stories just gave those ancient midwinter customs new religious meaning. It isn’t like that hasn’t happened elsewhere, as will be discussed further in this series of essays.

[Note: For further information about the potentially pagan roots of fire and light as a thematic focus for Hanukkah, and the evolution of the hanukkiah, see this article by Elon Gilad from the Israeli newspaper Haaretz. For a more thorough and scholarly analysis of the references to Hanukkah in the many writings by the first century CE Judeo-Roman historian priest, scholar and historian Flavius Josephus, and the sole reference to the holidays in the Christian New Testament (John 10:22) written about the same time, see this article by Prof. Gary J. Goldberg.]

Share this post