Hanukah Dance Today is the last evening of Hanukkah, when all of the hanukkiah candles will be burning bright. I had intended that today I would feature lively songs and klezmer music to honour this year’s conclusion of the ancient joyous festival. I knew at least one of those songs would come from The Klezmatics’ wonderful and important 2006 album Happy Joyous Hanukkah. But when this subdued, relaxed-paced interpretation of one of Woody Guthrie’s lesser-known songs from that album brought tears to my eyes every time I heard it I knew I had the right song for today.

They weren’t tears of sadness; they brought to the fore my increasingly-distant memories of my own daughters when they were young, and of my grandchildren who are just the right age now for this song.

The Klezmatics were formed in Coney Island in 1986 and are still going strong as one of the world’s best and most versatile klezmer bands. They have recorded 13 albums, and their music is easy to find on Spotify, YouTube, or wherever you go to explore new musical frontiers.

Essay: The Jewish side of Woody Guthrie

Okay, I admit it, that title is misleading. Woody Guthrie wasn’t Jewish, but he does have strong Jewish connections.

Woody was born and raised in Okemah, a small rural town in Okfuskee County Oklahoma where he was raised as an Evangelical Christian. Throughout his life, Woody was quite bookish and from a young age he studied the Bible diligently, both the Old and New Testaments. He came to be an admirer of Jesus Christ and His teachings, but developed a scorn for all organized religions. Throughout his adult life he never considered himself to be a member of any religion. When he had to fill out forms asking for his religion he would answer either all or none.

In 1945 Woody married Marjorie Greenblatt, a dancer with the Martha Graham Company (where her stage name was Marjorie Mazia.) Marjorie was the company’s top instructor and was one of the very few people from whom Graham took criticism. At the time, such ethnic/religious mixed marriages were very rare.

They bought a house in the immigrant Jewish neighbourhood of Coney Island in Brooklyn, across Mermaid Street from Marjorie’s mother the renowned Yiddish poet and activist Aliza Greenblatt, a key figure in the 20th century Yiddish literary revival. That neighbourhood was New York’s hotbed of Jewish culture and political activism.

Woody became very close friends with his mother-in-law despite having backgrounds that could hardly be different. They found common ground through their shared love of culture and social justice, and their shared inclinations to use artistic expression as a way to address political issues. According to Woody and Marjorie’s son Arlo they would discuss their writing projects with each other and critique each other’s work.

Through Marjorie and Aliza, Woody had a fast-track into Brooklyn’s Jewish artistic, literary and activist political communities. His well-established anti-fascist and pro-union credentials, as well as his reputation fame in folk music circles, gave him instant credibility. But because of his Okie accent I suspect that many of them were surprised when they found he could hold his own in their lively discussions. However, as far as I know Woody never learned Yiddish.

I have not found evidence that either Aliza or Marjorie were religiously devout, but they were deeply immersed in Jewish culture and heritage. Despite his antipathy to organized religion Woody readily accepted that his children with Marjorie should be raised as Jews, and he became quite interested in Jewish religion, history and culture, and Eliza, Marjorie and his new Jewish friends helped him study up on contemporary Jewish issues.

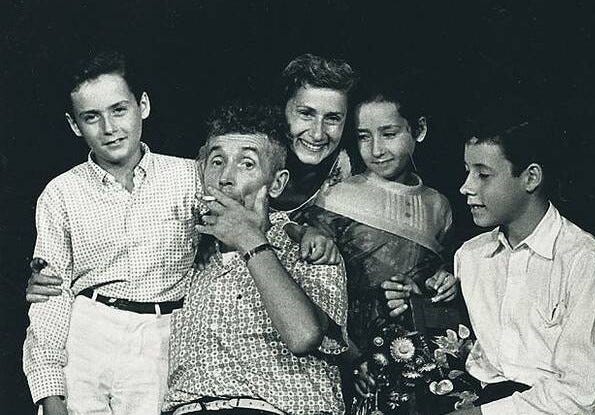

In the meantime, Woody was a loving father to a growing family. As any father knows, that involves making up songs that are engaging for them as they grow up. The family embraced the new format for celebrating a child-centered joyous Hanukkah that was discussed in Friday’s newsletter.

With a mother who was a professional dancer and a father who is a folk music legend, and everyone in the family being musicians, there was a more-than-average component of music and dancing. According to their children Arlo and Nora, after the candle lighting, and besides their dreidels and gelt, the children would dance around the Hanukkah tree until they fell asleep. And after they were down, their parents would continue with music and animated discussion with friends late into the night.

In the latter 1940s Woody began a new career as a children's entertainer. This included performing songs for parties at the Jewish Community Center. With Marjorie’s help (because Woody had never been very strict about tempo) he recorded four successful albums of children's music for Mose Asch's Folkways Records.

Woody and Mose had been long-time friends, beginning when Woody recorded over 100 songs for him in 1941. As with Marjorie and Aliza, they had similar political views and discussed progressive and radical politics when the recorder wasn’t running. In 1949 they began a fifth children’s album that was to feature songs from Woody’s Hanukkah repertoire. But that project was never completed and the only two such songs that he recorded became forgotten in Folkways’ vault of unreleased recordings.

In 1986, Folkways’ founder and owner Mose Asch died. The Smithsonian Museum recognized the importance of the company’s catalogue in documenting America’s musical heritage. They sought to acquire both ownership and publication rights to all of Folkways’ recordings, released and unreleased, as well as all of its business files. Negotiations for this acquisition had begun when Mose was still alive. The Smithsonian agreed to his condition that all of its 2,168 released albums would stay in print indefinitely, regardless of market sales.

When the archivists began studying the unreleased recordings they found many unreleased songs that Woody had recorded for Folkway. Obviously, the folk music community eagerly wanted to hear them so they began to release curated albums. In 1998, Smithsonian Folkways released Woody Guthrie Hard Travelin’, subtitled The Asch Recordings Vol 3. That album includes his short rendition of this song (click below) and his only other recorded Hanukkah song, a twenty-verse ballad about the holiday’s origin called The Many and The Few, both believed to have been recorded in 1949.

I don’t know if Nora Guthrie’s discovery in her father’s papers of lyrics (but not the melody) to six more Woody Guthrie Hanukkah songs was related to the Smithsonian’s discovery of the unreleased songs he recorded. Online I have found three different dates for when that is supposed to have happened – 1997, ‘98 and 2003. She is the family member who took responsibility to ensure the preservation of Woody’s legacy, and was the founder and President of the Woody Guthrie Foundation and Archives, who held his many handwritten notebooks.

My guess is that Smithsonian archivists would have consulted with Nora soon after they found the recordings to get contextual information. If such a consultation had occurred between the two archival organizations it might have inspired Nora to begin to look through Woody’s 3000 or so handwritten songs. They were all without music, and most had never been recorded. She found several on Jewish themes, but only six more songs related to Hanukkah.

It was in the Spring of 2003 that she approached The Klezmatics to develop settings and arrangements for the Jewish-theme songs, and to perform them. By Hanukkah of that same year they introduced songs from this source at a lavish Hanukkah concert in New York and Los Angeles in which Arlo Guthrie and the Celtic folk singer Susan McKeown also performed. The concerts were called Holy Ground: The Jewish Songs of Woody Guthrie.

It was three more years before The Klezmatics recorded their settings of the Jewish-theme Woody songs. I have not found if the settings and arrangements that were sung in that concert are the same ones the Klezmatics later used in their two 2006 albums. The answer is probably somewhere in this long Mudcat Discussion Forum thread but I don’t have time to look it up.

One of those albums is Wonder Wheel, which has non-Hanukkah songs. The other was the one that includes today’s version of Hanukah Dance. It was titled after one of the songs from their concert that was already going viral in America’s Jewish community: Happy Joyous Hanukkah.

The album includes the Klezmatics interpretation of the two songs recorded by Woody, the six songs that Nora found in Woody’s papers set and arranged by members of the band, and four original klezmer tunes. But the song Happy Joyous Hanukkah stands out for having become very popular and an instant classic of Hanukkah music, and is one of the few Hanukkah songs that is well-known in the non-Jewish world of Christmas music.

The lively melody and klezmer styling Lorin Sklamberg set for it seems perfect for the song to live up to its name. The irony that the lyrics for a hit Hanukkah song were written by a non-Jew won’t be lost on anyone who knows the authors of the enduring White Christmas, Chestnuts Roasting by an Open Fire, one about reindeer with a red nose, or who set Oh Holy Night to music.

I wonder what melody Woody had running through his head as he wrote the lyrics in his notebook? He had been living in that Jewish neighbourhood long enough that I suspect it probably was a klezmer tune.

Here is my personal favourite version of that instant Hanukkah classic, performed by the (not Jewish) Indigo Girls (Click on this image).

Share this post