Bethlehem, a fuguing tune version of While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks by Night, is performed here by the Washington Revels Chorus. It is from their 2014 album Sing & Rejoice.

The Revels are an American movement that promotes both community singing and an understanding and appreciation for seasonal customs and folklore. It began in Cambridge Massachusetts in 1971 with the formation of a community choir to present a costumed Christmas pageant. That has evolved. The pageants have grown ever more spectacular and events are now also held at different times of the year to tell how various cultures mark the changing seasons. Besides their pageants they have also expanded to additional other formats of entertainment, including parades and pub singing.

A;so, besides the original Cambridge organization there are now affiliated Revels groups in eight other American Cities. Watch this 3:12 minute video to learn more about the Revels movement. The Christmastime Revels remains the annual centrepiece for all of them. To date over two million people have attended their remarkably-grand live local midwinter performances.

With regard to this song itself, there are many, many different 18th and 19th century musical settings and arrangements for Nahum Tate’s (1692-1715) literal but poetic paraphrasing of the Nativity story in Luke 2:8-14. That is because his was the first, and for a long time the only, poetic translation of the Christmas story that was allowed to be sung in Anglican church services when music was again permitted after the Reformation (see the Christmas history essay I posted on December 5.) That is why many of the church’s new choir directors created their own settings and arrangements for Tate’s poem.

Also, the poem was written in the widely-used common meter which alternates between lines of eight and six syllables, and which always follows a stress pattern in which each unstressed syllable is followed by a stressed one. Many hymns and other songs are in common meter and their melodies and words can therefore be interchanged. Amazing Grace is an example of common meter: For fun, try singing While Shepherds Watched to its melody. With all that variety of melodies available, according to the music folklorist Dave Townsend: “At one time nearly every parish in England had its own distinctive version of this popular carol.” Most of the were long-forgotten, but in recent years people have developed an appreciation of their energetic style and non-standard harmonies and the old arrangements are being re-discovered and sung again.

When they wrote new settings for an existing hymn, composers of that era would often identify them in their songbooks by the name of the arrangement rather than by the name of their poetry. For some reason the composers often favoured place-names for their arrangements. That is why this is called Bethlehem instead of While hepherds Watched Their Flocks by Night.

The intent of that convention was to avoid confusion, but actually it now leads to confusion too since a lot of different composers used the same name for their arrangements. Sometimes the composers they even had multiple arrangements by the same name in different editions of their songbooks. In fact, that is the case with this one. This is just one of the arrangements that the American Revolutionary war era composer William Billings called Bethlehem, and a number of other composers also used the name Bethlehem for the tunes they wrote for Christmas hymns.

Billings (1746-1800) was a self-taught composer and choir director who lived in Boston. He wrote six volumes of music, and served as the choir director for churches of various protestant denominations. And those were just his side-gigs. His profession was as a tanner and he also held the civic post of scavenger (i.e., he collected dead animals from the streets).

His father died when he was 14 years old and he had to quit school to support his family. He had one eye, and one of his legs was shorter than the other. According to a contemporary description of him, Billings did not have a winning manner, but he did have a strong addiction to snuff and “. . . an uncommon negligence of person. Still, he spake & sung & thought as a man above the common abilities.” He was a good friend of the revolutionary instigator Sam Adams and the silversmith Paul Revere. I suspect the the reason that he had time for composing and choir directing was that like Paul Revere he had risen to a rather high status in his trade and was able to delegate much of the actual tanning and sales to his journeymen and apprentices.

Many of the post-Reformation choir directors and arrangers did not follow the classical rules for harmony and Billings was no exception. Although he had not been formally trained he was aware of what the classical rules were: He just chose to ignore them. He wrote: “I don’t think myself confined to any rules of composition laid down by any who went before me.” Billings is sometimes credited with having invented this fugue style of singing that became very popular for a while on both sides of the Atlantic.

The robust chorus of this song is a fugue. Note that this is different than the classical style of fuguing for choral music. (Sometimes it is spelled fuging to indicate the distinction.) It is based upon the singing style and harmonies of pub singing of that time. (Yes, they did harmony singing in pubs in those days!) It is unfortunate that such fugues have gone out of favour because they sure are fun to sing. (And the basses get to take the lead!)

To explain how fuguing works Wikipedia quotes musicologist George Pullen Jackson:

In the fuguing tune all the parts start together and proceed in rhythmic and harmonic unity usually for the space of four measures or one musical sentence. The end of this sentence marks a cessation, a complete melodic close. During the next four measures the four parts set in, one at a time and one measure apart. First the basses take the lead for a phrase a measure long, and as they retire on the second measure to their own proper bass part, the [tenors] take the lead with a sequence that is imitative of, if not identical with, that sung by the basses. The tenors in turn give way to the altos, and they to the trebles, all four parts doing the same passage (though at different pitches) in imitation of the [part in the] preceding measure. ... Following this fuguing passage comes a four-measure phrase, with all the parts rhythmically neck and neck, and this closes the piece; though the last eight measures are often repeated.

Fuguing is a lot easier to sing than to describe.

Star of Bethlehem is the name of the poem, not the melody. The arrangement was composed in 1808 by Englishman Charles W. Banister (1768-1831) who subtitled it “a new ode on the Nativity.” I was not able to find much information about him online. The lyrics were apparently from the posthumous publication of a poem by Henry Kirke White (1785-1806) who died of consumption at the age of 21.

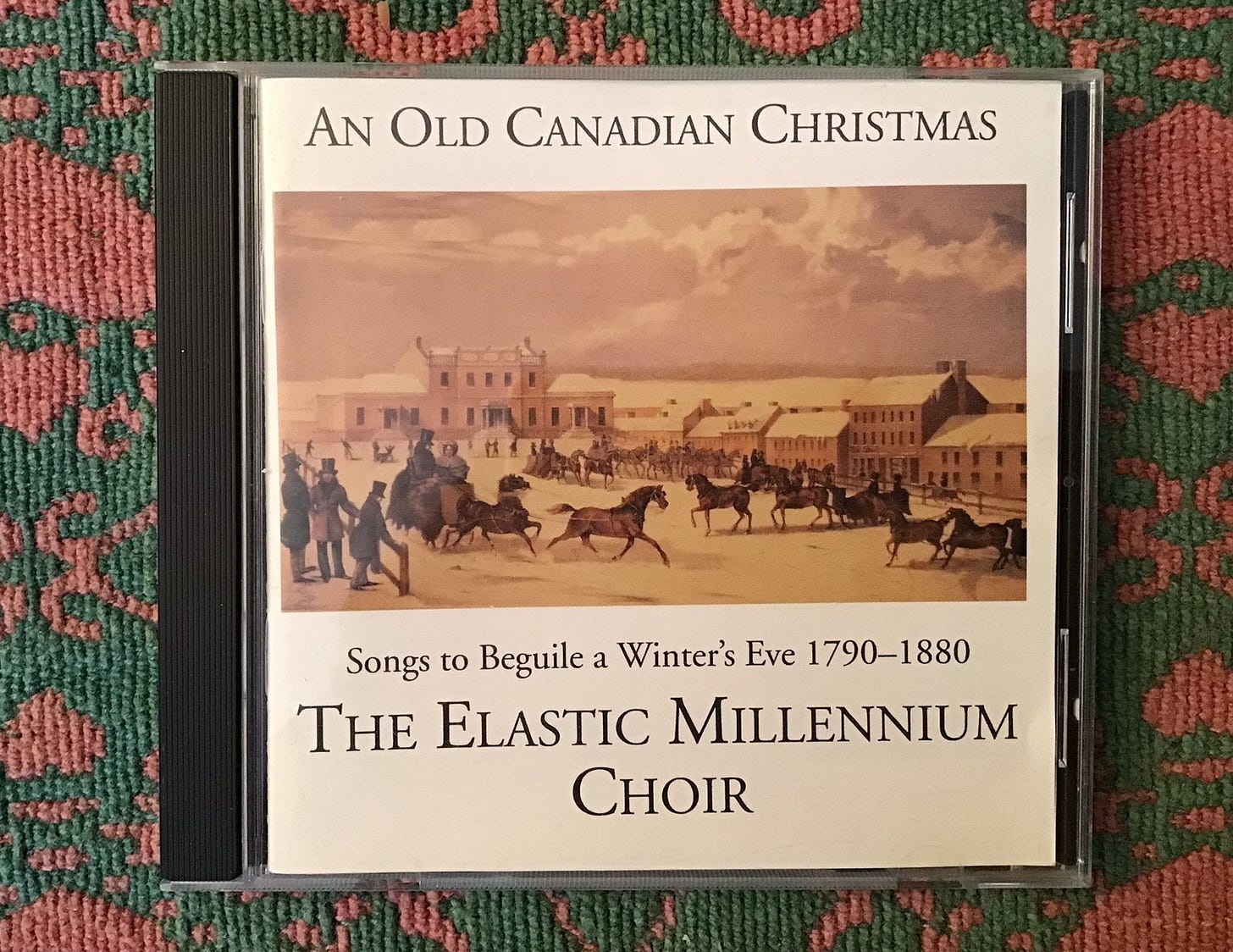

I got this recording from the 1997 album An Old Canadian Christmas self-published by the now-disbanded Elastic Millennium Choir of Halifax, Nova Scotia. This fabulous album is very rare and I was thrilled to be able to find the CD. What makes it special (besides the great performances) is that all of songs are from unpublished manuscripts or shape-note hymnbooks that had belonged to men who had run or been students of Canadian maritime province music schools during the shape-note era.

In this case, the song comes from a hymnbook called The Choir, published in 1879. The album’s liner notes have this to say about that hymnbook:

Presbyterian congregations in Nova Scotia had endured a series of disputes over the particular texts most appropriate for singing in church. They had been using [a hymnbook called] The Harmonicon up until the 1870s, but that book emphasized a less refined style and accorded less reverence to the actual texts. Some Presbyterians regarded the use of the psalms in singing schools and practices as blasphemous. The Choir was published under the auspices of the Presbyterian Synod to satisfy the need for a truly denominational book.

You will notice that Star of Bethlehem is quite different from other shapenote songs I have presented in my collections. In the context of that style of music it is both an anthem and an ode. In shapenote terminology, an anthem is a setting of words from the bible, a prayer book or other sacred writing. They are generally long and include changes in key. According to the Rudiments of Music essay which is the introduction to the ”red book” version of The Sacred Harp: “An ode is a musical setting of a poem of noble sentiment and dignity of style, especially one commemorating or honouring a particular subject, such as a person or special occasion.”

This anthem and ode is sung by a quartet from the Elastic Millennium Choir comprised of bass Charles Banting, soprano Michèle Raymond, alto Ditta Kasdan and tenor Kim Davison.

Share this post