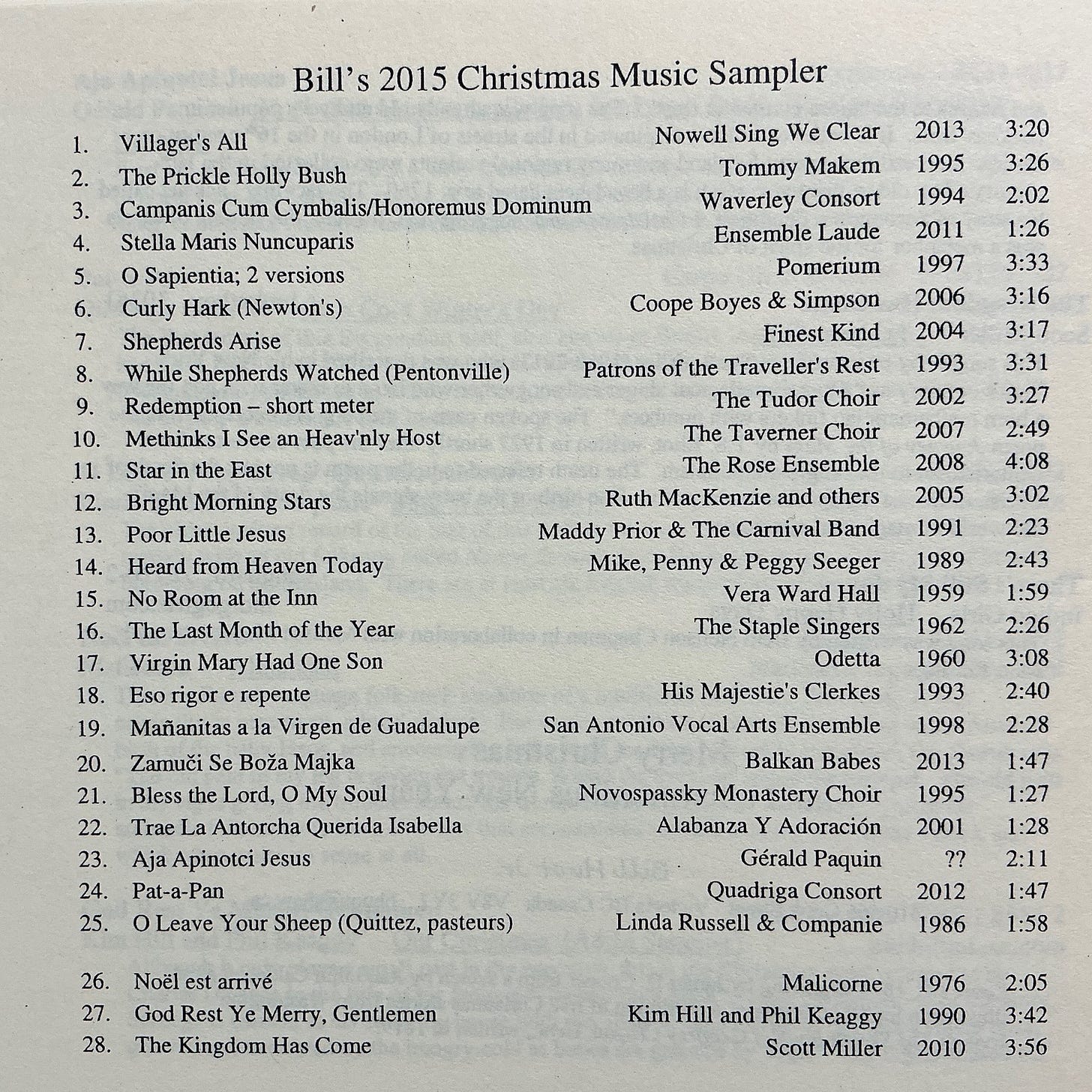

Playlist:

Villager’s All Nowell Sing We Clear 3:20

Redemption (Behold the Grace Appears) abridged The Tudor Choir 1:40

Shiloh (Methinks I See an Heav’nly Host) abridged The Taverner Choir 1:08

Mañanitas a la Virgen de Guadalupe San Antonio Vocal Arts Ensemble 2:28

Aja Apinotci Jesus Gérald Paquin 2:27

Noël est arrivé Malicorne 2:05

There’s Still My Joy Indigo Girls 2:46

Music notes

Villager’s All Kenneth Grahame's children's novel The Wind in the Willows was published in 1908. The story includes an episode in which field mice come caroling at Mole End. At the time when the novel was written both caroling and its older cousin wassailing were still common practices in rural England. This is the song that the mice sang. The word “benison” means blessings. (I had to look it up.)

This recording is from Nowell Sing We Clear’s 2013 album Bidding You Joy. The book does not include a melody for the song. Here, the words from the book have been set to music by Nowell Sing We Clear's Andy Davis. I feel a little guilty including another of their songs in these 15 minute song-breaks since I had one of theirs in yesterday’s mail-out, and another one two days before that. But I have bought all six of their CDs to draw from, as well as their great songbook for reference, so I have a lot of songs from them and they have a lot of great seasonal songs.

Here are the lyrics from Kenneth Grahame's book:

Carol of the Field Mice

by Kenneth GrahameVillagers all, this frosty tide,

Let your doors swing open wide,

Though wind may follow, and snow beside,

Yet draw us in by your fire to bide;

Joy shall be yours in the morning!Here we stand in the cold and the sleet,

Blowing fingers and stamping feet,

Come from far away you to greet—

You by the fire and we in the street—

Bidding you joy in the morning!Goodman Joseph toiled through the snow—

Saw the star o’er a stable low;

Mary she might not further go—

Welcome thatch, and litter below!

Joy was hers in the morning!And then they heard the angels tell

‘Who were the first to cry NOWELL?

Animals all, as it befell,

In the stable where they did dwell!

Joy shall be theirs in the morning!’

Redemption (Behold the Grace Appears) abridged The Puritan movement in 17th century England led the Church of England to turn away from all things considered to be Catholic. Harmony singing was one of the things considered to be too papist. The new order required church services to be simple, even austere, allowing only the slow singing of psalms in unison. Harmony singing was still around in the rural areas (at least in those towns and regions with royalist leanings) but it was in community gatherings, pubs and people's homes, not in the churches.

In the 18th century, reforms began and congregational hymn singing in the local language slowly began to be permitted. But Puritan settlers in New England had brought with them the insistence on musical simplicity in their church services, of course as as well as a complete absence of the English pub-singing tradition.

Slowly, the New England churches began to adopt similar reforms to those in England, but they faced the same problem that the English churches had faced: After over a century of prohibition there were no classically-trained choir directors or hymnists. But the appeal of singing, and doing it in harmony, was irrepressible. As had happened in the old country, people who were not classically trained stepped in to write three- or four-part hymn arrangements.

In New England, at about the time of the Revolutionary War this kind of hymn singing became a musical fad. People began to supplement church services to get their harmonic fixes. Music schools and travelling camp meetings emerged in which song leaders traveled to various nearby communities to bring harmony singing to the people (and sell the hymnbooks that they had written or compiled.) After that war, when many royalists emigrated north, the same fad came to Canada.

A new form of musical notation called shape notes was developed to help the musically-illiterate public learn the new choral arrangements. Notes made of triangles, ovals, rectangles and diamonds represented fa, sol, la and mi. The singers would sing the notes first, either to learn their parts or refresh their memories, before embarking on the lyrics.

Shape-note harmony singing, now often called sacred harp singing (the human voice was considered to be “the sacred harp” and that is the name of the most popular shape-note songbook) continues today, and it is another of my musical interests. Our Victoria Sacred Harp group meets twice a month at the Friends (Quaker) meetinghouse. Although the lyrics in our songbook, the Denson edition of The Sacred Harp, are mostly old religious hymns, for most of us this is a revival of a type of folk music rather than a form of worship.

This song is one of the New England hymns that lives on in the sacred harp singing tradition. The words are were written sometime before 1709 by “the father of English hymnody” Isaac Watts, who pioneered in writing sing-able poems that could become lyrics that were theologically satisfactory for the (still resistant to hymns) Church of England. But the arrangement of this version of the hymn is by Jeremiah Ingalls, a Vermont farmer and cooper who had become one of the new breed of choral arrangers and a music teacher. It is from the 1803 version of his songbook The Village Harmony. Music scholars see some evidence that its melody comes from a folk tune. That happened a lot during that era, in England, Europe and in North America.

It is sung by Seattle’s The Tudor Choir and is on their 2002 album An American Christmas. I have sung with many of that choir’s members at weekend-long sacred harp singings and music festivals. In fact, it was at a sacred harp workshop at the Seattle Folklife Festival where I first became intrigued by this part of our collective folk music heritage.

The full song on the Tudor Choir’s album is about 3:30 long but I have taken the liberty of abbreviating it to only two verses. That is fully within the sacred harp singing tradition. I also removed their singing of the notes from the beginning. That is not in the tradition but it was necessary to fit two sacred harp songs into this 15 minute set. Another part of the tradition is that the choral pieces are named according to their choral harmony arrangements rather than by the name for their lyrics. Hence, this one is called Redemption rather than Behold the Grace Appears, the Promise is Fulfilled.

Shiloh (Methinks I See an Heav’nly Host) abridged William Billings (1746-1800) was a Boston tanner who held the civic post of scavenger (i.e., he was responsible for collecting dead animals from the streets.) He came from a poor family. His father had died when he was 14 years old and he had to quit school to support his family. Billings had one eye, and one of his legs was shorter than the other. According to a contemporary description of him he did not have a winning manner, but he did have a strong addiction to snuff and “… an uncommon negligence of person. Still, he spake & sung & thought as a man above the common abilities.”

He was a good friend of the revolutionary instigators Sam Adams and Paul Revere. In addition to his day job as a tanner and scavenger (or more likely, as the owner of the company that did those things) he became a self-taught composer, publishing six volumes of music, and he served as the choir director for several churches of various protestant denominations.

Billings usually did arrangements for established texts, such as the poetry of Isaac Watts, but he wrote the words to this one himself and it is in his hymnbook The Suffolk Harmony published in 1786. This is one of two arrangement that he published for these lyrics. He had earlier used almost exactly the same text (and defended its lyrics vigorously) under the title Boston in his 1778 songbook The Singing Master’s Assistant. It is performed here by The Taverner Choir under the direction of Andrew Parrott and is from their 2007 album Festive Music from Europe and America.

Mañanitas a la Virgen de Guadalupe In 1531, only ten years after Cortez' conquest of the Aztecs, a devout Indian convert named Juan Diego reported that the Virgin Mary had appeared to him in a remote village called Guadalupe, on an Island off the west coast of Mexico. He said that Mary spoke to him in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs. Guadalupe had previously been thought of as the home of an Aztec goddess called Tonantzin, which means “our mother.” But the appearance was verified to the satisfaction of church authorities by a number of reported miracles, and the event proved to be instrumental in converting many more of the local people to Christianity.

This folk song dates from that time. Originally it was in Nahuatl, but this version is in Mexican Spanish. It translates as:

O lovely Virgin of the valley,

your children come to greet you in the morning.

Awaken and see the beautiful flowers I have brought to you.

That happy morning when you appeared to Juan began our life.

The song is performed by the now-disbanded San Antonio Vocal Arts Ensemble and is on their 1998 album Guadaloupe Virgen de los Indios.

Aja Apinotci Jesus The traditional French noël Il est né, le devine Enfant, which probably originated in the 18th century, is sung here in by the Quebec based singer-songwriter Gérald Paquin. He sings it in Anishinaabemowin, the language of the Ojibwe people. He had learned that language when he was a child and his mother was a teacher at a residential school.

In a 2019 Radio Canada interview he said (translated by Google): “I was practicing [Il est né] at home, you know at my cottage. I was just practicing with my drum and it was like, hey, this sounds a little bit indigenous.” I got this recording from a Radio Canada charitable fund-raising compilation album called Christmas from Home / Noël chez nous.

The first documentation of Il est né, le devine Enfant is in a compilation of noëls from the Lorraine region of northeastern France published in 1862. The melody is a much earlier folk tune known as La tête bizarde (the bizarre head).

Noël est arrivé This is a French language folk-rock rendition of a traditional noël from Provence, on the Mediterranean in south-eastern France. It was originally in provençal, the local dialect. The verses are about shepherds spreading the word about the birth of the baby Jesus, and encouraging folks to go see him. Roughly translated, the chorus says:

The old pain in my leg is giving me trouble.

Sound the trumpet; sound the trumpet.

The old pain in my leg is giving me trouble.

Sound the trumpet upon my horse.

It is very typical for French folk songs to have choruses that are unrelated to what is being said in the verses, and which often make no sense at all.

The song is performed by the now-disbanded French folk-rock group Malicorne, who formed in 1973 and were very popular through the rest of the 1970s. They first disbanded in early 1982, and briefly reformed a few times over the next two decades but could not return to their former glory. This was recorded at the height of their fame in 1976 and is from their album Almanach which musically traces the changing seasons.

There’s Still My Joy This song was written by Beth Neilson Chapman in collaboration with Melissa Manchester and Matt Rollings. It is performed here by the American folk rock music duo Indigo Girls, comprised of Amy Ray and Emily Saliers who had met in grade school. It is from their (great!) 2010 album Holly Happy Days on Vanguard Records. They began performing together in 1985 and are still active – or perhaps I should say very active. They are renowned for their support for social justice causes, which also gets them into controversies in their home base of Atlanta, Georgia. Here is a published interview if you want to learn more about them.

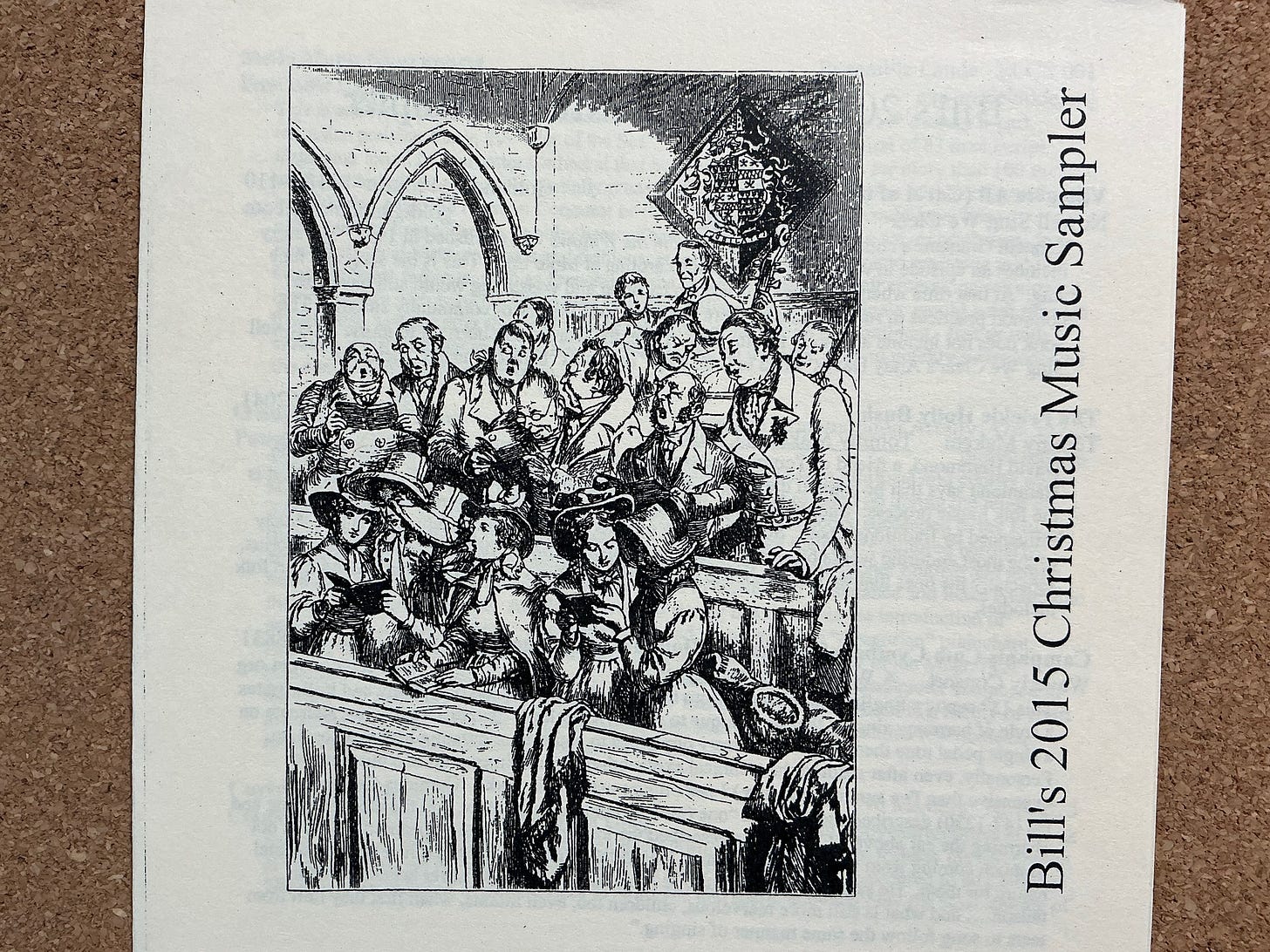

Sampler-making recollections

2015 was in the middle of when I was taking this hobby project most seriously. I don’t have any strong memories of compiling this one, so there must have been nothing particularly dramatic about it. I probably did most of the planning and song selection in the summertime.

You may have noticed that I return to mostly-nativity compilations quite frequently. That was only partly to keep my father happy, but mostly because that is what a lot of the best Christmas music is. Way too many renditions of secular Christmas songs come across to me as being motivated by pop music commercial considerations. Maybe it is just that good singers are also good actors, but I am looking for sensitive songs that seem to come from the heart, and I find that characteristic most frequently in Nativity songs.

Also, many nativity songs use folk melodies that got frozen-in-time when they were used as settings for hymns or Christmas carols before their folksong lyrics faded into oblivion or the melodies evolved with continually-changing musical fashions. These tunes have been polished by the folk process, while pop Christmas songs are usually written by the same professional songwriters who write the bulk of other pop songs. They just insert their same pop music sentiments into a Christmas season song and the songs get protected from the folk process by copyright complications.

The structure of this sampler follows my common three movement format. Villagers All was its opening song, as it is here, and There’s still My Joy is the closing song on both the sampler and here. Those are the places where I usually like to put especially meaningful songs. The former, along with Tommy Makem’s The Prickle Holly Bush, made for a strong opening for the CD. There’s Still My Joy is both thoughtful and reflective, and has an ending that makes it a perfect closer.

In between the “movements” are; old choral harmony singing, solo spirituals, and traditional international nativity songs in various languages (usually not the one in which they were written.)

Share this post